文章信息

- 刘亚辉,缪景霞,李黎波,李爱民,罗荣城. 2015.

- LIU Yahui, MIAO Jingxia, LI Libo, Li Aimin, LUO Rongcheng. 2015.

- 高迁移率族蛋白B1在肿瘤发生发展中的作用

- Clinical Analysis of Multimodality Treatments for Pancreatic Cancer Patients with Liver Metastases

- 肿瘤防治研究, 2015, 42(07): 730-736

- Cancer Research on Prevention and Treatment, 2015, 42(07): 730-736

- http://www.zlfzyj.com/CN/10.3971/j.issn.1000-8578.2015.07.019

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2014-10-28

- 修回日期:2015-01-15

2.510515广州,南方医科大学南方医院肿瘤科

2.Oncology Department,Nanfang Hospital,Southern Medical University,Guangzhou 510515,China

2011年,Hanahan和Weinberg更新他们的癌症中心理论[1],提出促进癌症发生的十大基本特性:支持增殖信号、回避生长抑制、逃避免疫损害、无限制生长、促肿瘤炎症、侵袭和转移、血管生成、基因不稳定和突变、抵抗细胞坏死、异常细胞代谢,而这些特征与高迁移率族蛋白B1(high mobility group box 1,HMGB1)的定位和过表达密切相关,所以把HMGB1放在现代理解癌症生物学的核心位置。HMGB1被强调在许多肿瘤中起关键作用[2],包括肾癌、肺癌、胰腺癌、胃癌、结直肠癌、肝癌、乳腺癌、前列腺癌、宫颈癌、血液系统肿瘤及黑色素瘤等。HMGB1在肿瘤中的"双刃剑"作用,目前认为最重要的原因是其在肿瘤细胞中的翻译后修饰,翻译后修饰决定HMGB1在细胞中的定位及功能[3]。

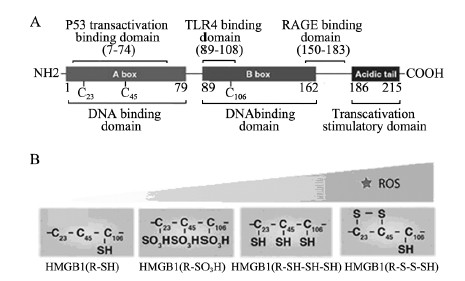

1 HMGB1的结构 1.1 一级结构HMGB1是由215个氨基酸残基组成的单链多肽,含两个DNA结合域:A-box (9~79氨基酸序列)、B-box (95~163氨基酸序列)及C-tail (186~215氨基酸序列),DNA结合域是维持DNA有效弯曲和折叠所必须的。在细胞中,C-tail的缺失使HMGB1与DNA及蛋白质结合疏松;缺少C-tail的HMGB1过表达阻止各种靶向基因的表达。细胞外的B-box引起炎性反应,而A-box具有抗炎活性,且与C-tail结合后能够增强A-box的抗炎活性[4]。细胞外HMGB1能结合一些蛋白,他们之间的相互作用对HMGB1的激活和功能起着重要作用:7~74氨基酸序列负责结合p53反式激活域引起相关基因转录;89~108氨基酸序列结合TLR4引起炎性反应;150~183氨基酸序列负责结合RAGE引起细胞迁移,见图 1。

|

| TLR4:Toll-like receptor 4;RAGE:receptor for advanced glycation end products;ROS:reactive oxygen species;A:primary structure of HMGB1;B:the change of redox status and tertiary structure of HMGB1 along with the increase of ROS 图 1 高迁移率族蛋白B1的结构 Figure 1 Structure of high-mobility group box 1(HMGB1) protein |

HMGB1的二级结构主要与DNA的结合和改变DNA弯曲度及染色质重组有关[5]。

1.3 三级结构HMGB1结合域中的三个半胱氨酸(Cys23、Cys45、Cys106)与C-ail相互作用维系着HMGB1的三级结构,Cys106被丝氨酸替代后引起HMGB1由胞核进入胞质。Cys23与Cys45可通过氧化折叠过程形成分子内二硫键[6]。不同程度氧化的HMGB1分别与不同的受体和DNA结合,发挥迥然不同的作用,所以细胞氧化环境的改变可以改变HMGB1的氧化修饰从而影响HMGB1的结构、定位及功能[7]。

2 HMGB1翻译后修饰目前发现HMGB1的翻译后修饰有6种形式:乙酰化、腺苷二磷酸(ADP)-核糖基化、甲基化、磷酸化和氧化,这些修饰在HMGB1的定位及功能中起重要作用,其中决定其功能最主要的修饰为氧化修饰;糖基化,HMGB1糖基化数量极少,其功能不明确[8]。

2.1 乙酰化HMGB1可在赖氨酸2、11及81序列上(Lys2、Lys11、Lys81)上发生乙酰化,乙酰化的HMGB1与DNA结合力增加[9],与同源的DNA多聚酶α相互作用介导DNA的复制。在LPS、IFN、丁酸钠及低氧等多种刺激下,HMGB1发生乙酰化,随后进入胞质并通过出胞作用释放至胞外,乙酰化可限制HMGB1再返入胞核。

2.2 ADP-糖基化HMGB1的ADP-核糖基化在肿瘤细胞中增加,是细胞死亡尤其是细胞坏死中介导HMGB1核输出和释放的必须形式。在细胞胞外,ADP-核糖基化HMGB1结合PS和RAGE,抑制胞吞作用,进一步加强炎性反应[10];在细胞内,ADP-糖基化HMGB1的缺乏导致多聚酶1(poly ADP-ribose polymerase 1,PARP1)的过度激活和损伤,进一步导致肝细胞死亡,这些发现提示在调节细胞死亡上面PARP1与HMGB1的ADP-核糖基化有交互作用[11]。

2.3 甲基化在透明肾细胞癌[1 2]、中性粒细胞[1 3]中,HMGB1中A-box构象改变导致甲基化,其结合DNA的活性明显降低,这一改变导致HMGB1由胞核进入胞质中,同时B-box上Lys112的单一甲基化也可使HMGB1发生核转位进入胞质。所以HMGB1可作为染色质组中甲基化药物作用靶点。

2.4 磷酸化磷酸化HMGB1与DNA结合/弯曲、胞核-胞质分布及释放有密切关系[14]。在体外实验中,PKC-磷酸化的HMGB1增加结肠癌细胞HMGB1的释放[15]。

2.5 氧化越来越多的证据表明HMGB1的定位及功能大部分取决于氧化修饰[6]。HMGB1一级结构内的Cys23/Cys45/Cys106,是氧化修饰的核心靶向氨基酸[16],这3个半胱氨酸可被多种氧化信号氧化成以下几种形式:氧化硫醇侧链(R-SH)、二硫酸盐(R-S-S-SH)、硫磺酸(R-SOH)、磺酸跟(R-SO3H)及全部硫醇型(R-SH-SH-SH),氧化后的HMGB1与非氧化HMGB1相比,与DNA结合变疏松,有利于释放至胞质、胞外。在活化的免疫细胞和损伤细胞中,最常见的氧化信号-活性氧(ROS)使HMGB1不同程度被氧化,在核内结合DNA紧密性下降从而促进HMGB1的转位和释放;同时,氧化修饰还影响HMGB1在细胞外的活动,包括免疫、自噬、炎性反应、肿瘤细胞生长、侵袭和转移及趋药性[17, 18]:(1)当ROS较少时,初级氧化型(R-SH) HMGB1分泌至胞外与RAGE结合,诱导周围肿瘤细胞发生自噬或调节细胞的迁移、生长和蛋白表达[19],使细胞适应各种不利环境。细胞自噬正反馈诱导更多HMGB1的胞外转移发挥作用。(2)当ROS增加、氧化损伤加重时,细胞发生凋亡。从氧化敏感的线粒体中释放的细胞色素C可进一步激活凋亡通路诱导凋亡;在凋亡晚期,氧化型HMGB1(R-SO3H)被释放,作为免疫抑制因子诱导树突状细胞的免疫耐受[20],如果HMGB1被Caspase1裂解并结合RAGE后,这一过程可被逆转[21];同时HMGB1(R-SO3H)可能有诱导凋亡的作用。(3)当ROS非常多,氧化损伤非常严重时,细胞坏死,细胞线粒体渗透性转变(MPT)或线粒体膜破裂,细胞崩解,此时两种形式的HMGB1渗漏至胞外:①二硫酸盐型HMGB1(S-S-SH),它与TLR4/MD2结合产生一系列细胞因子,促进炎性反应[22];②全部硫醇型HMGB1(SH-SH-SH),作为一趋化因子与CXCL12形成络合物后与CXCL4结合诱导趋化因子的生成,产生趋药性[19, 22]。

3 HMGB1与肿瘤相关的细胞定位及其功能 3.1 细胞核内功能(1) DNA伴侣:参与DNA复制、结合、损伤修复[23];维持端粒及染色体稳定性[24, 25];(2)调节多个靶向基因的转录[2];(3)通过调节HMGB1的转录调节自噬和凋亡[19]。

3.2 细胞质内功能(1)氧化还原反应传感器[6];(2)依赖外源性HMGB1调节细胞自噬,使细胞逃逸、免疫耐受、耐受化疗或放疗[19];(3)以出胞方式释放HMGB1[26]。

3.3 细胞外液功能氧化修饰后相关DAMP信号通路[17]:(1)简化型(R-SH):与RAGE结合,诱导周边细胞的发生依赖Beclin-1的自噬、对放疗或化疗耐药、或促进细胞的迁移、生长;(2) HMGB1(R-SO3H):作为免疫抑制因子诱导树突状细胞的免疫耐受,使肿瘤细胞逃过免疫反应,促进肿瘤发生;但也可结合RAGE诱导细胞凋亡,增加化疗及放疗细胞毒性;(3)二硫酸盐型HMGB1(S-S-SH):它与TLR4/MD2结合产生一系列细胞因子,促进炎性反应,促进侵袭和转移;(4)硫醇型HMGB1(SH-SH-SH):趋药活性,招募白血球,增加药物毒性,促进细胞死亡。

其他功能:(1)增强由巨噬细胞激活的NK细胞的IFN-γ的释放[27];(2)与其他细胞因子协同调节细胞功能[28];(3)与DC细胞的TIM3结合,降低抗肿瘤免疫反应[29]。

4 HMGB1与肿瘤 4.1 HMGB1与肾细胞癌在肾透明细胞癌中HMGB1表达增加[12]。HMGB1-RAGE通路通过激活ERK1/2在肾透明细胞癌进程中起促进作用[30]。

4.2 HMGB1与肺癌在非小细胞肺癌(NSCLC)中,HMGB1表达增加与疾病的进展、侵袭和转移有关,血清HMGB1水平可能成为NSCLC的生物标志物[31]。miR-218在肺癌中作为肿瘤抑制剂通过部分下调HMGB1表达从而减少转移[32]。HMGB1通过激活PI3K-AKT和NF-κB通路调节肺癌细胞MMP-9表达和细胞转移能力[33]。

4.3 HMGB1与胰腺癌在胰腺癌中血清HMGB1升高,化学药物治疗后也可见升高[34],从坏死细胞或免疫细胞释放的HMGB1通过结合RAGE促进ATP生成和胰腺癌细胞生长[35]。用RNA干扰技术或反义核苷酸沉默HMGB1或其受体RAGE可以抑制胰腺癌细胞的侵袭,通过降低自噬增加化疗药物的敏感度[36, 37, 38]。其受体RAGE的缺失可抑制致瘤基因K-RAS所致的胰腺癌变。这些研究提示HMGB1-RAGE通路在胰腺癌生长和治疗中起关键调节作用[36]。

4.4 HMGB1与胃癌在胃癌中,HMGB1mRNA和蛋白的表达均增高且与炎性状态有关。血清HMGB1水平是早期诊断胃癌的标志物[39]。HMGB1及RAGE的同时高表达加强NF-κB的活性促进胃癌的侵袭和转移[40, 41]。在化疗中,HMGB1介导的细胞自噬降低长春新碱引起的细胞凋亡,部分原因是通过上调Mcl-1,Mcl-1可使肿瘤细胞逃避凋亡[42]。然而,在抗癌治疗后,HMGB1的高表达却是预后良好因素[43]。这些结果提示HMGB1在胃癌的不同阶段发挥着不同的作用。

4.5 HMGB1与结肠直肠癌基因突变(APC、K-RAS、p53)、染色体不稳定、DNA修复力差和异常DNA甲基化被认为是结肠直肠癌发病的分子遗传基础,核内HMGB1可能是这些分子遗传基础的重要调节因子[44]。在结肠直肠癌患者中,HMGB1与肿瘤进展、迁移和预后差有关[45, 46, 47, 48];放射性栓塞治疗后HMGB1表达增加预示着疗效差[46]。腹部手术创伤后HMGB1的大量分泌促进结直肠癌术后腹膜转移[49]。坏死结肠癌细胞释放的HMGB1通过RAGE通路加强剩余肿瘤细胞的再生和转移[50]。在早期研究中提示细胞外HMGB1诱导巨噬细胞凋亡、阻止巨噬细胞浸润至结肠癌组织中,从而减弱宿主抗癌的免疫力[51],但另有研究提示奥沙利铂、氟尿嘧啶等化疗致肿瘤细胞释放的HMGB1可通过TLR4通路激活树突状细胞(DCs),然后加强T细胞的抗肿瘤免疫反应[52, 53]。在结肠癌中,沉默HMGB1增加化疗敏感度,部分原因可能是HMGB1下调后,p53介导的自噬和凋亡增加了[54]。Kikuchi等将能分泌HMGB1拮抗剂的间充质干细胞(MSCs)治疗荷瘤小鼠,肿瘤明显减少,提示着自体骨髓来源细胞有望成为一种新的治疗策略[55]。HMGB1的靶向治疗研究显示,应用RNA干扰、EP (丙酮酸乙酯)、乙酰半胱氨酸抑制HMGB1表达、释放和活性,可以抑制结肠癌转移性肝癌模型的肿瘤生长[56, 57]。

4.6 HMGB1与原发性肝癌(HCC)血清HMGB1水平在HCC患者中升高,并且HMGB1在肝脏的表达与肝癌病理分级、远处转移、耐药密切相关[58, 59, 60, 61]。在感染HCV或HBV的HCC患者中血清HMGB1比单纯的HCC患者明显升高[61]。低氧的肿瘤微环境释放HMGB1可与TLR4和RAGE结合,激活NFkB、AKT和炎性通路,促进HCC的侵袭和转移[57, 58, 59, 60, 61]。p53一般为肿瘤抑制因子,但在发展为肝癌过程中可能是HMGB1释放的正调节因子[62]。这些研究提示HMGB1在HCC的发展过程和治疗中起着关键性作用。

4.7 HMGB1与乳腺癌人类乳腺干细胞(CSCs)表面高表达TLR2和其配体HMGB1,介导CSCs的自我更新、肿瘤发生和转移能力[63]。对新辅助化疗有反应(CR或PR)的乳腺癌患者HMGB1升高,而治疗效果差(SD或PD)的患者新辅助化疗后HMGB1没有升高,表明早期动态变化的血清HMGB1水平可能是预测乳腺癌新辅助化疗最终效果的早期预测因子[64, 65]。体外实验中,miR-200c能抑制HMGB1表达从而减少乳腺癌细胞的侵袭和转移[66]。联合化疗导致转移性乳腺癌细胞释放的HMGB1介导了对肿瘤细胞起杀伤作用的自身免疫反应的激活[67]。这些研究提示可将HMGB1作为判断肿瘤治疗疗效的指标,并可能成为有价值的基因治疗靶点

4.8 HMGB1与前列腺癌在前列腺癌患者中,HMGB1和RAGE表达的增高与肿瘤进展及预后差相关,提示着RAGE和HMGB1可作为前列腺癌新的预后指标[68]。根治性前列腺癌术后高表达HMGB1提示预后差[69]。利用RNAi沉默HMGB1的配体RAGE可诱导肿瘤细胞凋亡、抑制肿瘤的生长[70]。大鼠前列腺癌形成过程中,HMGB1引发适应性免疫反应促进肿瘤的形成,提示着HMGB1可作为肿瘤预防和治疗的靶点[71]。

4.9 HMGB1与宫颈癌在宫颈上皮鳞状细胞癌(CSCC)患者中,HMGB1高表达与肿瘤侵袭和转移显著相关,HMGB1/RAGE通路在CSCC转移中起关键作用[72]。复发CSCC患者血清HMGB1水平明显高于无复发CSCC患者和健康对照组者,血清HMGB1可成为评估CSCC患者肿瘤复发和预测预后的因子,与其他因子联合检测可提高诊断特异性[73]。

4.10 HMGB1与血液恶性肿瘤在血液系统恶性疾病治疗过程中HMGB1可过表达,促进恶性细胞增殖,进而降低疗效;HMGB1与Beclin1、ERK、JNK等蛋白相互作用促进血液恶性肿瘤细胞自噬(外源性HMGB1则直接诱导自噬),参与化疗放疗抵抗。因此,通过抑制HMGB1表达,促进肿瘤细胞凋亡及增加血液病细胞对化疗药物的敏感度,是治疗血液恶性肿瘤的新策略[74]。动态变化HMGB1也可作为非霍奇金淋巴瘤(ALL)治疗效果的早期预测因子[75]。

4.11 HMGB1与黑色素瘤在黑色素瘤患者中,黑色素瘤标本中HMGB1表达明显高于正常组织或黑色痣组织,并且更高水平HMGB1与分级更高、预后更差相一致。进一步实验证明HMGB1在黑色素瘤中有着致瘤原性,有望成为黑色素瘤治疗靶点之一[76]。

5 结论及展望HMGB1最早报道于1973年,随着研究地深入,越来越多的功能被发现:从非组蛋白染色质结合蛋白到晚期、早期炎性因子,再到对肿瘤的双刃剑作用,尤其是近15年里,HMGB1的转录后修饰、定位及一系列受体被发现,细胞内外的HMGB1在肿瘤的发生发展中起着明显不同的作用,这些特性使其成为一个有意义的生物标志及治疗靶点[77]。许多针对HMGB1的肿瘤治疗研究如抑制HMGB1释放及活性正在进行中[78]。在鼠类模型HMGB1的条件性敲除研究中,得到了有关HMGB1在肿瘤作用中复杂甚至相反的结论[11, 79, 80]。未来在HMGB1定位、结构、转录后修饰及相关作用分子的研究,将解开HMGB1在肿瘤发生发展中复杂作用之谜。

| [1] | Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation[J]. Cell, 2011, 144(5): 646-74. |

| [2] | Tang D, Kang R, Zeh HJ 3rd, et al. High-mobility group box 1 and cancer[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2010, 1799(1-2): 131-40. |

| [3] | Kang R, Zhang Q, Zeh HR, et al. HMGB1 in cancer: good, bad, or both?[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2013, 19(15): 4046-57. |

| [4] | Gong W, Zheng Y, Chao F, et al. The anti-inflammatory activity of HMGB1 A box is enhanced when fused with C-terminal acidic tail[J]. J Biomed Biotechnol, 2010: 915234. |

| [5] | Gerlitz G, Hock R, Ueda T, et al. The dynamics of HMG proteinchromatin interactions in living cells[J]. Biochem Cell Biol, 2009, 87(1): 127-37. |

| [6] | Tang D, Kang R, Zeh HJ 3rd, et al. High-mobility group box 1, oxidative stress, and disease[J]. Antioxid Redox Signal, 2011, 14(7): 1315-35. |

| [7] | Tang D, Billiar TR, Lotze MT. A Janus tale of two active high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) redox states[J]. Mol Med, 2012, 18: 1360-2. |

| [8] | Chao YB, Scovell WM, Yan SB. High mobility group protein, HMG-1, contains insignificant glycosyl modification[J]. Protein Sci, 1994, 3(12): 2452-4. |

| [9] | Elenkov I, Pelovsky P, Ugrinova I, et al. The DNA binding and bending activities of truncated tail-less HMGB1 protein are differentially affected by Lys-2 and Lys-81 residues and their acetylation[J]. Int J Biol Sci, 2011, 7(6): 691-9. |

| [10] | Davis K, Banerjee S, Friggeri A, et al. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) protein enhances inhibition of efferocytosis[J]. Mol Med, 2012, 18: 359-69. |

| [11] | Huang H, Nace GW, McDonald KA, et al. Hepatocyte-specific high-mobility group box 1 deletion worsens the injury in liver ischemia/reperfusion: a role for intracellular high-mobility group box 1 in cellular protection[J]. Hepatology, 2014, 59(5): 1984-97. |

| [12] | Wu F, Zhao ZH, Ding ST, et al. High mobility group box 1 protein is methylated and transported to cytoplasm in clear cell renal cell carcinoma[J]. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev, 2013, 14(10): 5789-95. |

| [13] | Ito I, Fukazawa J, Yoshida M. Post-translational methylation of high mobility group box 1(HMGB1) causes its cytoplasmic localization in neutrophils[J]. J Biol Chem, 2007, 282(22): 16336-44. |

| [14] | Kang HJ, Lee H, Choi HJ, et al. Non-histone nuclear factor HMGB1 is phosphorylated and secreted in colon cancers[J]. Lab Invest, 2009, 89(8): 948-59. |

| [15] | Lee H, Park M, Shin N, et al. High mobility group box-1 is phosphorylated by protein kinase C zeta and secreted in colon cancer cells[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2012, 424(2): 321-6. |

| [16] | Sahu D, Debnath P, Takayama Y, et al. Redox properties of the A-domain of the HMGB1 protein[J]. FEBS Lett, 2008, 582(29): 3973-8. |

| [17] | Li G, Tang D, Lotze MT. Menage a Trois in stress: DAMPs, redox and autophagy[J]. Semin Cancer Biol, 2013, 23(5): 380-90. |

| [18] | Venereau E, Casalgrandi M, Schiraldi M, et al. Mutually exclusive redox forms of HMGB1 promote cell recruitment or proinflammatory cytokine release[J]. J Exp Med, 2012, 209(9): 1519-28. |

| [19] | Tang D, Kang R, Cheh CW, et al. HMGB1 release and redox regulates autophagy and apoptosis in cancer cells[J]. Oncogene, 2010, 29(38): 5299-310. |

| [20] | Kazama H, Ricci JE, Herndon JM, et al. Induction of immunological tolerance by apoptotic cells requires caspasedependent oxidation of high-mobility group box-1 protein[J]. Immunity, 2008, 29(1): 21-32. |

| [21] | LeBlanc PM, Doggett TA, Choi J, et al. An immunogenic peptide in the A-box of HMGB1 protein reverses apoptosis-induced tolerance through RAGE receptor[J]. J Biol Chem, 2014, 289(11): 7777-86. |

| [22] | Balosso S, Liu J, Bianchi ME, et al. Disulfide-containing high mobility group box-1 promotes N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor function and excitotoxicity by activating Toll-like receptor 4-dependent signaling in hippocampal neurons[J]. Antioxid Redox Signal, 2014, 21(12): 1726-40. |

| [23] | Lotze MT, Tracey KJ. High-mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1): nuclear weapon in the immune arsenal[J]. Nat Rev Immunol, 2005, 5(4): 331-42. |

| [24] | Giavara S, Kosmidou E, Hande MP, et al. Yeast Nhp6A/B and mammalian Hmgb1 facilitate the maintenance of genome stability[J]. Curr Biol, 2005, 15(1): 68-72. |

| [25] | Polanská E1, Dobšáková Z, Dvo?áčková M, et al. HMGB1 gene knockout in mouse embryonic fibroblasts results in reduced telomerase activity and telomere dysfunction[J]. Chromosoma, 2012, 121(4): 419-31. |

| [26] | Krysko O, Løve Aaes T, Bachert C, et al. Many faces of DAMPs in cancer therapy[J]. Cell Death Dis, 2013, 4:e631. |

| [27] | DeMarco RA, Fink MP, Lotze MT. Monocytes promote natural killer cell interferon gamma production in response to the endogenous danger signal HMGB1[J]. Mol Immunol, 2005, 42(4): 433-44. |

| [28] | Yanai H, Ban T, Taniguchi T. High-mobility group box family of proteins: ligand and sensor for innate immunity[J]. Trends Immunol, 2012, 33(12): 633-40. |

| [29] | Chiba S, Baghdadi M, Akiba H, et al. Tumor-infiltrating DCs suppress nucleic acid-mediated innate immune responses through interactions between the receptor TIM-3 and the alarmin HMGB1[J]. Nat Immunol, 2012, 13(9): 832-42. |

| [30] | Lin L, Zhong K, Sun Z, et al. Receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) partially mediates HMGB1-ERKs activation in clear cell renal cell carcinoma[J]. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol, 2012, 138(1): 11-22. |

| [31] | Shang GH, Jia CQ, Tian H, et al. Serum high mobility group box protein 1 as a clinical marker for non-small cell lung cancer[J]. Respir Med, 2009, 103(12): 1949-53. |

| [32] | Zhang C, Ge S, Hu C, et al. miRNA-218, a new regulator of HMGB1, suppresses cell migration and invasion in non-small cell lung cancer[J]. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai), 2013, 45(12): 1055-61. |

| [33] | Liu PL, Tsai JR, Hwang JJ, et al. High-mobility group box 1-mediated matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression in non-small cell lung cancer contributes to tumor cell invasiveness[J]. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol, 2010, 43(5): 530-8. |

| [34] | Wittwer C, Boeck S, Heinemann V, et al. Circulating nucleosomes and immunogenic cell death markers HMGB1, sRAGE and DNAse in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer undergoing chemotherapy[J]. Int J Cancer, 2013, 133(11): 2619-30. |

| [35] | Kang R, Tang D, Schapiro NE, et al. The HMGB1/RAGE inflammatory pathway promotes pancreatic tumor growth by regulating mitochondrial bioenergetics[J]. Oncogene, 2014, 33(5): 567-77. |

| [36] | Kang R, Tang D. Autophagy in pancreatic cancer pathogenesis and treatment[J]. Am J Cancer Res, 2012, 2(4): 383-96. |

| [37] | Kang R, Tang D, Livesey KM, et al. The receptor for advanced glycation end-products(RAGE) protects pancreatic tumor cells against oxidative injury[J]. Antioxid Redox Signal, 2011, 15(8): 2175-84. |

| [38] | Kang R, Tang D, Loze MT, et al. Apoptosis to autophagy switch triggered by the MHC class Ⅲ-encoded receptor for advanced glycation endproducts(RAGE)[J]. Autophagy, 2011, 7(1): 91-3. |

| [39] | Chung HW, Lee SG, Kim H, et al. Serum high mobility group box- 1(HMGB1) is closely associated with the clinical and pathologic features of gastric cancer[J]. J Transl Med, 2009, 7: 38. |

| [40] | Zhang J, Kou YB, Zhu JS, et al. Knockdown of HMGB1 inhibits growth and invasion of gastric cancer cells through the NFkappaB pathway in vitro and in vivo[J]. Int J Oncol, 2014, 44(4): 1268-76. |

| [41] | Zhang J, Zhu JS, Zhou Z, et al. Inhibitory effects of ethyl pyruvate administration on human gastric cancer growth via regulation of the HMGB1-RAGE and Akt pathways in vitro and in vivo[J]. Oncol Rep, 2012, 27(5): 1511-9. |

| [42] | Zhan Z, Li Q, Wu P, et al. Autophagy-mediated HMGB1 release antagonizes apoptosis of gastric cancer cells induced by vincristine via transcriptional regulation of Mcl-1[J]. Autophagy, 2012, 8(1): 109-21. |

| [43] | Bao G, Qiao Q, Zhao H, et al. Prognostic value of HMGB1 overexpression in resectable gastric adenocarcinomas[J]. World J Surg Oncol, 2010, 8: 52. |

| [44] | Breikers G, van Breda SG, Bouwman FG, et al. Potential protein markers for nutritional health effects on colorectal cancer in the mouse as revealed by proteomics analysis[J]. Proteomics, 2006, 6(9): 2844-52. |

| [45] | Süren D1, Yıldırım M2, Demirpençe Ö, et al. The role of high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) in colorectal cancer[J]. Med Sci Monit, 2014, 20: 530-7. |

| [46] | Fahmueller YN, Nagel D, Hoffmann RT, et al. Immunogenic cell death biomarkers HMGB1, RAGE, and DNAse indicate response to radioembolization therapy and prognosis in colorectal cancer patients[J]. Int J Cancer, 2013, 132(10): 2349-58. |

| [47] | Wiwanitkit V. Expression of HMG1 and metastasis of colorectal cancer[J]. Int J Colorectal Dis, 2010, 25(5): 661. |

| [48] | Yao D, Brownlee M. Hyperglycemia-induced reactive oxygen species increase expression of the receptor for advanced glycation end products(RAGE) and RAGE ligands[J]. Diabetes, 2010, 59(1): 249-55. |

| [49] | Li W, Wu K, Zhao E, et al. HMGB1 recruits myeloid derived suppressor cells to promote peritoneal dissemination of colon cancer after resection[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2013, 436(2): 156-61. |

| [50] | Luo Y, Chihara Y, Fujimoto K, et al. High mobility group box 1 released from necrotic cells enhances regrowth and metastasis of cancer cells that have survived chemotherapy[J]. Eur J Cancer, 2013, 49(3): 741-51. |

| [51] | Aychek T, Miller K, Sagi-Assif O, et al. E-selectin regulates gene expression in metastatic colorectal carcinoma cells and enhances HMGB1 release[J]. Int J Cancer, 2008, 123(8): 1741-50. |

| [52] | Fang H, Ang B, Xu X, et al. TLR4 is essential for dendritic cell activation and anti-tumor T-cell response enhancement by DAMPs released from chemically stressed cancer cells[J]. Cell Mol Immunol, 2014, 11(2): 150-9. |

| [53] | Tesniere A, Schlemmer F, Boige V, et al. Immunogenic death of colon cancer cells treated with oxaliplatin[J]. Oncogene, 2010, 29(4): 482-91. |

| [54] | Livesey KM, Kang R, Zeh HJ 3rd, et al. Direct molecular interactions between HMGB1 and TP53 in colorectal cancer[J]. Autophagy, 2012, 8(5): 846-8. |

| [55] | Kikuchi H, Yagi H, Hasegawa H, et al. Therapeutic potential of transgenic mesenchymal stem cells engineered to mediate antihigh mobility group box 1 activity: targeting of colon cancer[J]. J Surg Res, 2014, 190(1): 134-43. |

| [56] | Cheng P, Ni Z, Dai X, et al. The novel BH-3 mimetic apogossypolone induces Beclin-1- and ROS-mediated autophagy in human hepatocellular carcinoma[corrected] cells[J]. Cell Death Dis, 2013, 4: e489. |

| [57] | Cheng P, Dai W, Wang F, et al. Ethyl pyruvate inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma via regulation of the HMGB1-RAGE and AKT pathways[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2014, 443(4): 1162-8. |

| [58] | Xiao J, Ding Y, Huang J, et al. The association of HMGB1 gene with the prognosis of HCC[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(2): e89097. |

| [59] | Jiang W, Wang Z, Li X, et al. Reduced high-mobility group box 1 expression induced by RNA interference inhibits the bioactivity of hepatocellular carcinoma cell line HCCLM3[J]. Dig Dis Sci, 2012, 57(1): 92-8. |

| [60] | Dong YD, Cui L, Peng CH, et al. Expression and clinical significance of HMGB1 in human liver cancer: Knockdown inhibits tumor growth and metastasis in vitro and in vivo[J]. OncolRep, 2013, 29(1): 87-94. |

| [61] | Jiang W, Wang Z, Li X, et al. High-mobility group box 1 is associated with clinicopathologic features in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Pathol Oncol Res, 2012, 18(2): 293-8. |

| [62] | Yan HX, Wu HP, Zhang HL, et al. p53 promotes inflammationassociated hepatocarcinogenesis by inducing HMGB1 release[J]. J Hepatol, 2013, 59(4): 762-8. |

| [63] | Conti L, Lanzardo S, Arigoni M, et al. The noninflammatory role of high mobility group box 1/Toll-like receptor 2 axis in the self-renewal of mammary cancer stem cells[J]. FASEB J, 2013, 27(12): 4731-44. |

| [64] | Arnold T, Michlmayr A, Baumann S, et al. Plasma HMGB-1 after the initial dose of epirubicin/docetaxel in cancer[J]. Eur J Clin Invest, 2013, 43(3): 286-91. |

| [65] | Stoetzer OJ, Fersching DM, Salat C, et al. Circulating immunogenic cell death biomarkers HMGB1 and RAGE in breast cancer patients during neoadjuvant chemotherapy[J]. Tumour Biol, 2013, 34(1): 81-90. |

| [66] | Chang BP, Wang DS, Xing JW, et al. miR-200c inhibits metastasis of breast cancer cells by targeting HMGB1[J]. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci, 2014, 34(2): 201-6. |

| [67] | Buoncervello M, Borghi P, Romagnoli G, et al. Apicidin and docetaxel combination treatment drives CTCFL expression and HMGB1 release acting as potential antitumor immune response inducers in metastatic breast cancer cells[J]. Neoplasia, 2012, 14(9): 855-67. |

| [68] | Zhao CB, Bao JM, Lu YJ, et al. Co-expression of RAGE and HMGB1 is associated with cancer progression and poor patient outcome of prostate cancer[J]. Am J Cancer Res, 2014, 4(4): 369-77. |

| [69] | Li T, Gui Y, Yuan T, et al. Overexpression of high mobility group box 1 with poor prognosis in patients after radical prostatectomy[J]. BJU Int, 2012, 110(11 Pt C): E1125-30. |

| [70] | Elangovan I, Thirugnanam S, Chen A, et al. Targeting receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) expression induces apoptosis and inhibits prostate tumor growth[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2012, 417(4): 1133-8. |

| [71] | He Y, Zha J, Wang Y, et al. Tissue damage-associated “danger signals” influence T-cell responses that promote the progression of preneoplasia to cancer[J]. Cancer Res, 2013, 73(2): 629-39. |

| [72] | Hao Q, Du XQ, Fu X, et al. Expression and clinical significance of HMGB1 and RAGE in cervical squamous cell carcinoma[J]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi, 2008, 30(4): 292-5.[郝权, 杜晓琴, 付欣, 等. 高迁移率族蛋白1及晚期糖基化终产物受体在宫颈鳞 状细胞癌中的表达及临床意义[J]. 中华肿瘤杂志, 2008, 30(4): 292-5.] |

| [73] | Sheng X, Du X, Zhang X, et al. Clinical value of serum HMGB1 levels in early detection of recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of uterine cervix: comparison with serum SCCA, CYFRA21-1, and CEA levels[J]. Croat Med J, 2009, 50(5): 455-64. |

| [74] | Hu YH, Yang L, Zhang CG, et al. HMGB1--a as potential target for therapy of hematological malignancies review[J]. Zhongguo Shi Yan Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi, 2014, 22(2): 560-4.[胡亚会, 杨璐, 张晨光, 等. HMGB1——血液恶性肿瘤治疗的潜在靶点[J]. 中 国实验血液学杂志, 2014, 22(2): 560-4.] |

| [75] | Kang R, Tang DL, Cao LZ, et al. High mobility group box 1 is increased in children with acute lymphocytic leukemia and stimulates the release of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in leukemic cell[J]. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi, 2007, 45(5): 329-33.[康睿, 唐道 林, 曹励之, 等. 急性淋巴细胞性白血病患儿血清高迁移率族蛋 白1检测及其诱导白血病细胞分泌肿瘤坏死因子α的实验研究[J]. 中华儿科杂志, 2007, 45(5): 329-33.] |

| [76] | Li Q, Li J, Wen T, et al. Overexpression of HMGB1 in melanoma predicts patient survival and suppression of HMGB1 induces cell cycle arrest and senescence in association with p21 (Waf1/Cip1) up-regulation via a p53-independent, Sp1-dependent pathway[J]. Oncotarget, 2014, 5(15): 6387-403. |

| [77] | Andersson U, Tracey KJ. HMGB1 is a therapeutic target for sterile inflammation and infection[J]. Annu Rev Immunol, 2011, 29: 139-62. |

| [78] | Musumeci D, Roviello GN, Montesarchio D. An overview on HMGB1 inhibitors as potential therapeutic agents in HMGB1- related pathologies[J]. Pharmacol Ther, 2014, 141(3): 347-57. |

| [79] | Ge X, Antoine DJ, Lu Y, et al. High-Mobility Group Box-1 (HMGB1) Participates in the Pathogenesis of Alcoholic Liver Disease (ALD)[J]. J Biol Chem, 2014, 289(33): 22672-91. |

| [80] | Tang D, Kang R, Van Houten B, et al. HMGB1 Phenotypic Role Revealed with Stress[J]. Mol Med, 2014, 20: 359-62. |

2015, Vol. 42

2015, Vol. 42