文章信息

- 王晗,倪娟,周滔,汪旭.

- WANG Han, NI Juan, ZHOU Tao, WANG Xu.

- 叶酸对正常人成纤维细胞及黑色素瘤细胞端粒长度及基因组稳定性的影响

- Effect of Folic Acid on Telomere Length and Genome Stability of Normal Human Fiber Cell and Melanoma Cell in vitro

- 肿瘤防治研究, 2015, 42(12): 1188-1191

- Cancer Research on Prevention and Treatment, 2015, 42(12): 1188-1191

- http://www.zlfzyj.com/CN/10.3971/j.issn.1000-8578.2015.12.004

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2015-03-26

- 修回日期: 2015-06-15

2. 650500 昆明,云南师范大学生物能源持续开发与利 用教育部工程研究中心

2. Engineering Research Center of Sustainable Development and Utilization of Biomass Energy, Ministry of Education, Yunnan Normal University, Kunming 650500, China

端粒(Telome r e)是真核生物染色体末端TTAGGG串联重复序列及端粒结合蛋白构成的核蛋白复合物,完整功能结构的端粒能防止染色体末端融合及结构重排,维护染色体的稳定[1, 2]。端粒会随每次细胞分裂缩短50~150 bp,当端粒缩短达到一定长度后,细胞将停止分裂,进入复制衰老,启动凋亡[3, 4, 5]。端粒极短时细胞继续存活,则可能出现染色体融合等染色体畸变并积累突变,增加遗传相关的疾病危险度[6, 7, 8]。目前,端粒的结构功能已逐渐成为退行性疾病如肿瘤、心血管和神经系统疾病、风湿性关节炎等的重要生物指标[9, 10, 11, 12]。85%的肿瘤细胞通过端粒酶(Telomerase)来维持端粒长度,促进细胞增殖、侵袭和抑制凋亡,避免复制衰老,达到细胞永生[13]。

在大量人类和动物的研究中,端粒长度已被证实与营养状况及膳食相关。叶酸(folate acid,FA)是一碳单位代谢中的重要微营养素,对维持DNA正确复制及DNA甲基化至关重要[14]。叶酸缺乏情况下,通常会导致尿嘧啶大量积累,并代替胸腺嘧啶掺入DNA分子,在随后的损伤修复过程中导致DNA链断裂、染色体损伤以及细胞恶变,端粒DNA由于富含胸腺嘧啶,被尿嘧啶替代的几率较高,此外,叶酸也可能通过影响端粒及端粒旁的甲基化修饰对端粒长度进行调节[12, 15]。依据体外培养中维持人淋巴细胞基因组结构稳定的中度叶酸缺乏浓度(30 nmol/L)、最适叶酸浓度(120 nmol/L)[16]以及正常RPMI 1640培养液中叶酸浓度(2 260 nmol/L),本实验以30~3 000 nmol/L氧化态合成叶酸改组的RPMI1640培养液对人正常皮肤来源的成纤维细胞株BJ及癌变皮肤来源的黑色素瘤细胞株A375进行21天干预培养,采用O’Callaghan等[17]改进的RT-qPCR技术分析端粒绝对长度(absolute telomere length,aTL),胞质分裂阻断微核细胞实验(CBMNCyt)[18]分析基因组稳定性,比较不同叶酸浓度对不同细胞株端粒长度及基因组稳定性的影响,为寻找维护端粒长度及基因组稳定性的叶酸浓度、微营养素矫正遗传损伤、降低退行性疾病危险度提供科学依据。

1 材料与方法1.1 细胞株与材料人正常皮肤成纤维细胞株BJ购自广州吉妮欧生物科技有限公司(ATCC® CRL-2522™);黑色素瘤细胞株A375购自中国科学院昆明动物研究所细胞库(ATCC® CRL-1619™);受试细胞培养于RPMI1640培养液(5%FBS,1%双抗,2 mmol/L L-谷氨酰胺,pH7.0)中,取对数生长期细胞干预培养。无叶酸RPMI 1640培养液购自美国Gibco公司,FBS购自澳大利亚Gibco公司,基因组DNA提取试剂盒购自北京天根生化技术有限公司,Power SYBRGreen master mix购自英国ABI公司,FA及细胞松弛素B(Cytochalasin B,CB)购自美国Sigma公司。

1.2 实验方法1.2.1 细胞干预培养以无叶酸RPMI 1640培养液(5% FBS,1%双抗,2 mmol/L L-谷氨酰胺,pH7.0)配制含30、100、300、1 000及3 000 nmol/L的FA干预培养液,分别干预培养BJ及A375细胞21天,每三天更换一次培养液,第9、15及21天取出的一部分细胞用于提取各干预组核DNA分析aTL,另一部分细胞用于CBMN-Cyt分析染色体不稳定性(chromosomalinstability,CIN)。

1.2.2 RT-qPCR分析端粒长度采用RT-qPCR进行端粒绝对长度测量,测量基因组拷贝数的单拷贝基因选用36B4。PCR所需引物、标准品序列及测量方法参考O’Callaghan等[17]的方法。

待测样本及标准曲线均在ABI StepOne plus实时荧光定量PCR仪上进行反应。反应结束后,系统依据标准曲线给每个样品分别生成两个值,即每个目标样本的端粒总长度(kb/reaction)和基因组拷贝数(基因组拷贝数/reaction),二者的比率就是样本的端粒绝对长度(TL/diploid genome,kb)。

1.2.3 CBMN- Cyt分析染色体不稳定性不同时间取样的部分细胞加入CB(终浓度为4.5 μg/ml)继续培养28 h,收集细胞涂片、固定、染色并封片。光学显微镜下分析CBMN-Cyt指标,即双核细胞(binucleated cell,BNC)中微核(micronuclei,MN)、核质桥(nucleoplasmic bridges,NPB)及核芽(nuclear bud,NBud)的分析及发生频率(‰),三者频率加起来得到细胞的CIN,指标形态学判断及计算参考Fenech等[18]的方法。

1.3 统计学方法实验数据用SPSS17.0软件进行分析,单因素方差分析不同叶酸浓度对BJ细胞及A375细胞的端粒长度、CIN指标影响,Duncan检验进行多重比较; P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。GraphPad Prism 5软件作图。

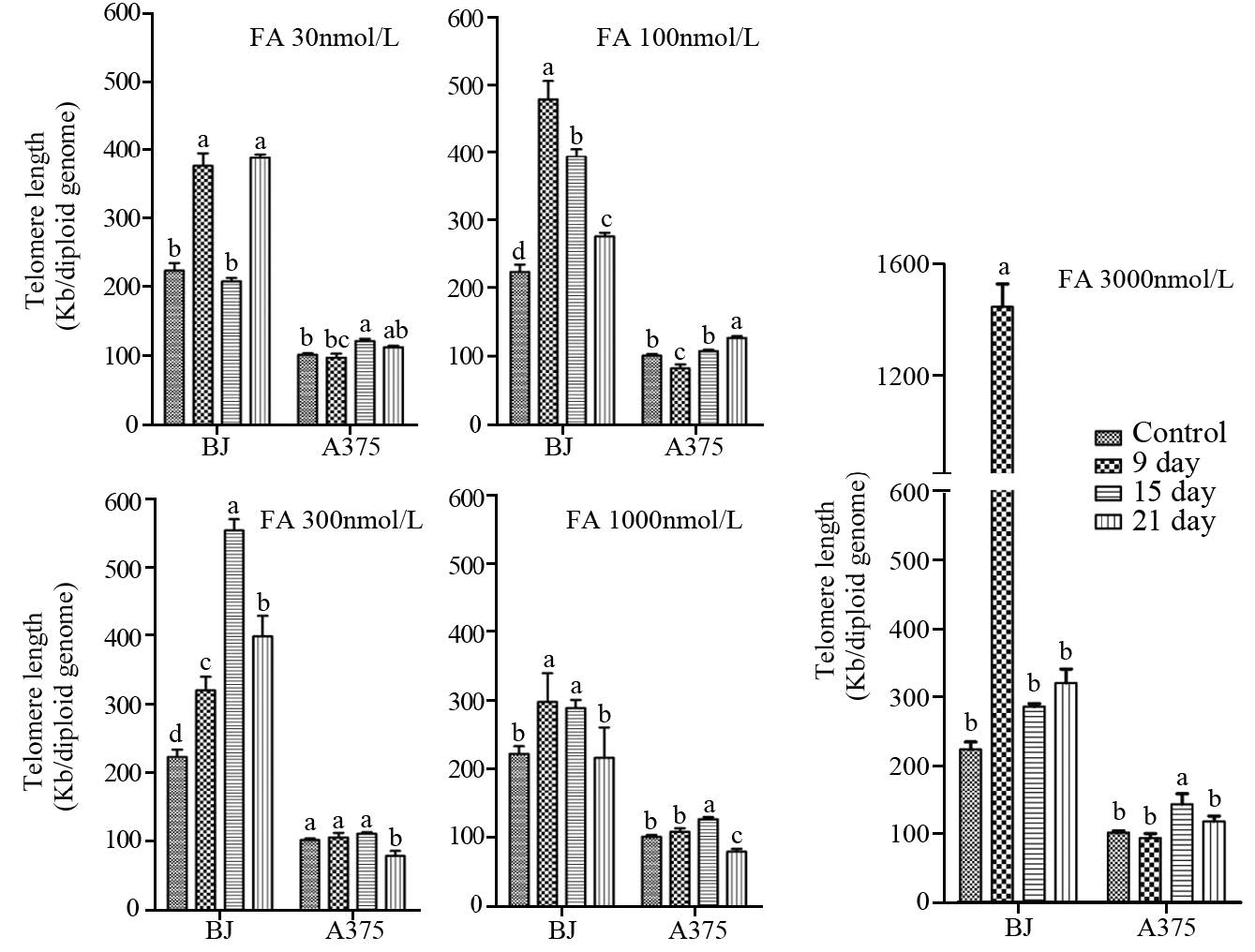

2 结果2.1 叶酸干预后受试细胞端粒长度改变不同浓度FA干预培养BJ及A375细胞后,端粒长度改变,见图 1。

BJ细胞在FA 30 nmol/L,端粒长度随培养时间延长出现无规律波动,在FA 100~1 000 nmol/L,端粒随干预时间延长而较对照组显著增加,尤其在FA 3 000 nmol/L,9天培养时,端粒长度是对照组的6倍( P<0.001)。在FA 100~300 nmol/L,端粒长度与FA浓度呈明显正相关(r=0.451, P<0.001),而随干预时间延长,在2 1 天时端粒明显缩短( P<0.001)。在FA 1000 nmol/L时,随干预时间延长,端粒长度的变化幅度小于其余干预组。A375细胞的端粒长度随干预时间延长也出现波动,但整体波动幅度较BJ细胞小。在FA 100nmol/L,A375细胞的端粒长度在9天培养时较对照显著缩短( P=0.02),随干预时间延长,端粒显著增长( P=0.01)。在FA 30、300~3 000nmol/L,A375细胞的端粒长度均在15天时增长( P<0.05),21天时明显缩短( P<0.05)。

|

| a,b,c,d: P<0.001-0.05, bars sharing different letters were significant different from each other. Letters came from one-way ANOVA(Duncan multiple comparison) 图 1 不同浓度叶酸干预后BJ及A375细 胞端粒长度改变的比较 Figure 1 Comparison of telomere length change in BJ and A375 cells at different concentration of folic acid |

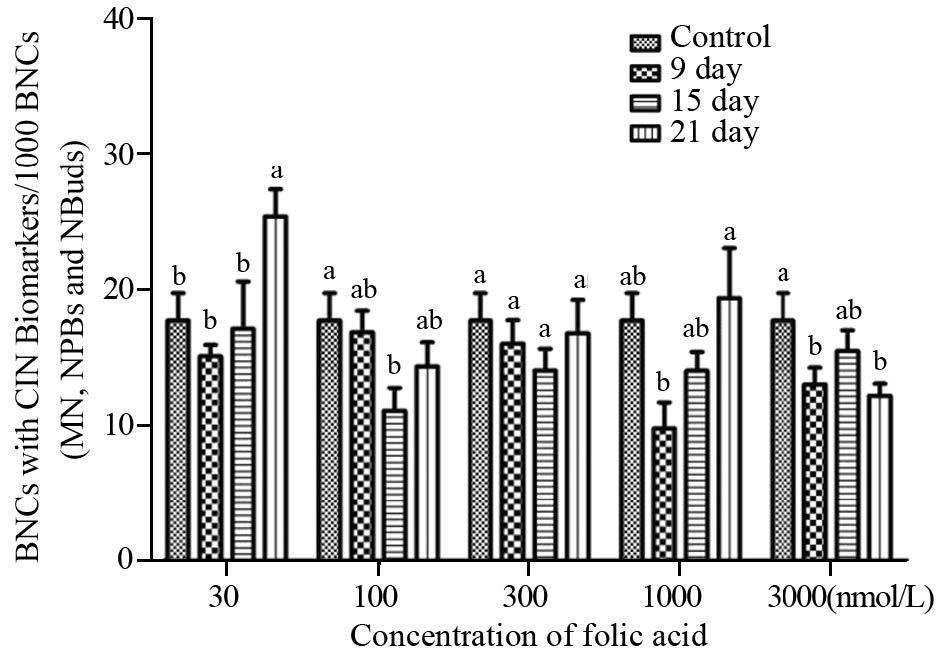

BJ细胞在FA 30~300及3 000 nmol/L,随干预时间延长,CIN率均较对照显著上升( P<0.05),其中,FA 30 nmol/L时,CIN率达到最大值。在FA 1 000nmol/L,随干预时间延长,CIN率改变无显著性差异,见图 2。

|

| a,b,c,d: P<0.001-0.05, bars sharing different letters were significant different from each other. Letters came from one-way ANOVA(Duncan multiple comparison) 图 2 BJ细胞CIN率在不同叶酸干预下的改变情况 Figure 2 Changes of the CIN rate in BJ cells on different FA concentrations |

A375细胞在FA 30 nmol/L,随干预时间延长,21天时CIN率较对照显著上升( P=0.013);在FA100、1 000、3 000 nmol/L,9天或15天培养时CIN率显著低于对照( P<0.05),而第15天、21天时长,CIN率有所上升。在FA 300 nmol/L,CIN率维持不变,见图 3。

|

| a,b,c,d: P<0.001-0.05, bars sharing different letters were significant different from each other. Letters came from one-way ANOVA(Duncan multiple comparison)图 3 A375细胞CIN率在不同叶酸干预下的改变情况 Figure 3 Changes of the CIN rate in A375 cells on different FA concentrations |

端粒缩短或延长导致的端粒结构功能改变,容易触发DNA损伤应答,造成染色体末端切除或末端融合,引起基因组不稳定性及相关疾病发生。人正常体细胞中,端粒通过感知复制压力,对基因组完整性控制有调停的作用,通过触发p53依赖的凋亡发生,消除衰老及基因组不稳定的细胞,维持机体内环境稳定,降低疾病发生[19, 20]。多数癌细胞来源于端粒极度缩短的复制衰老期细胞,它们能绕过细胞周期p53/pRB通路检查点,通过端粒酶的重新激活来维持端粒长度,避免因端粒消耗而使细胞进入凋亡,逃离细胞危机期,进入癌变过程,因而可能保持稳定的短端粒状态[5, 21, 22, 23]。研究结果显示,端粒酶阳性细胞A375在任何FA 干预下,其端粒长度均无法达到端粒酶阴性细胞BJ的水平,端粒长度变化较BJ小,且端粒长度和CIN率对叶酸浓度的升高无依赖性,推测A375因端粒酶的表达,较BJ细胞具有短却稳定的端粒长度。

BJ细胞在叶酸缺乏(30 nmol/L)时,端粒长度随干预时间延长呈现不稳定增长或缩短,CIN率明显升高,提示正常细胞中叶酸缺乏可能引起端粒或亚端粒序列低甲基化,造成端粒不稳定延长,也可能引发DNA损伤切除修复或染色体末端断裂、融合而引起端粒缩短或丧失[12],二者均与基因组不稳定性呈正相关。在FA 100~300 nmol/L,BJ细胞的端粒长度和CIN率与FA浓度呈现正相关,提示BJ细胞端粒的延长依赖于叶酸,而端粒持续增长后明显缩短可能引起端粒结构和功能的改变,与基因组不稳定性相关。FA 1 000 nmol/L时,BJ细胞的端粒长度和CIN率维持不变,提示1 000 nmol/L的叶酸适宜维护BJ细胞全基因组甲基化状态及DNA完整性。值得注意的是,在高FA (3 000 nmol/L)状态时,BJ细胞随干预时间延长,端粒长度变化较大,CIN率明显上升,推测高叶酸对正常细胞可能具有某种毒性。

综上,研究认为,黑色素瘤细胞A375的端粒和基因组稳定性变化对叶酸无明显依赖,而正常皮肤成纤维细胞BJ因叶酸缺乏易引起端粒的异常和基因组稳定性下降,提示不同转化状态的细胞对叶酸缺乏具有不同的响应机制。

| [1] | Williams JM, Ouenzar F, Lemon LD, et al. The principal role of Kuin telomere length maintenance is promotion of Est1 associationwith telomeres[J]. Genetics, 2014, 197(4): 1123-36. |

| [2] | Pal J, Gold JS, Munshi NC, et al. Biology of telomeres: importancein etiology of esophageal cancer and as therapeutic target[J].Transl Res, 2013, 162(6): 364-70. |

| [3] | Shen M, Cawthon R, Rothman N, et al. A prospective study oftelomere length measured by monochrome multiplex quantitativePCR and risk of lung cancer[J]. Lung Cancer, 2011, 73(2): 133-7. |

| [4] | Renaud S, Loukinov D, Abdullaev Z, et al. Dual role of DNAmethylation inside and outside of CTCF-binding regions in thetranscriptional regulation of the telomerase hTERT gene[J].Nucleic Acids Res, 2007, 35(4): 1245-56. |

| [5] | Shay JW, Wright WE. Role of telomeres and telomerase incancer[J]. Semin Cancer Biol, 2011, 21(6): 349-53. |

| [6] | Jones MJ, Jallepalli PV. Chromothripsis: chromosomes in crisis[J].Dev Cell, 2012, 23(5): 908-17. |

| [7] | Hartwig FP, Bertoldi D, Larangeira M, et al. Up-RegulatingTelomerase and Tumor Suppressors: focusing on anti-aginginterventions at the population level[J]. Aging and Dis, 2014, 5(1):17-26. |

| [8] | Willeit P, Willeit J, Mayr A, et al. Telomere length and risk ofincident cancer and cancer mortality[J]. JAMA, 2010, 304(1):69-75. |

| [9] | Martínez P, Blasco MA. Telomeric and extra-telomeric roles fortelomerase and the telomere-binding proteins[J]. Nat Rev Cancer,2011, 11(3): 161-76. |

| [10] | Harte AL, da Silva NF, Miller MA, et al. Telomere length attrition,a marker of biological senescence, is inversely correlated withtriglycerides and cholesterol in South Asian males with type 2diabetes mellitus[J]. Exp Diabetes Res, 2012, 2012: 895185. |

| [11] | Mitteldorf JJ. Telomere biology: Cancer firewall or agingclock?[J]. Biochemistry (Mosc), 2013, 78(9): 1054-60. |

| [12] | Moores CJ, Fenech M, O’Callaghan NJ. Telomere dynamics: theinfluence of folate and DNA methylation[J]. Ann N Y Acad Sci,2011, 1229(1): 76-88. |

| [13] | Zhou J, Ding D, Wang M, et al. Telomerase reverse transcriptasein the regulation of gene expression[J]. BMB Rep, 2014, 47(1):8-14. |

| [14] | Paul L. Diet, nutrition and telomere length[J]. J NutritionalBiochem, 2011, 22(10): 895-901. |

| [15] | Liu J J, Prescott J, Giovannucci E, et al. One-carbon metabolismfactors and leukocyte telomere length[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2013,97(4): 794-9. |

| [17] | O’Callaghan NJ, Fenech M. A quantitative PCR method formeasuring absolute telomere length[J]. Biol Proced Online, 2011,13:3. |

| [18] | Fenech M. Cytokinesis-block micronucleus cytome assay[J]. NatProtoc, 2007, 2(5): 1084-104. |

| [19] | Günes C, Rudolph KL. The role of telomeres in stem cells andcancer[J]. Cell, 2013, 152(3): 390-3. |

| [20] | Gallardo F, Laterreur N, Wellinger RJ, et al. Telomerase caught inthe act: united we stand, divided we fall[J]. RNA Biol, 2012, 9(9):1139-43. |

| [21] | Bernardes de Jesus B, Blasco MA. Telomerase at the intersectionof cancer and aging[J]. Trends Genet, 2013, 29(9): 513-20. |

| [22] | Fairlie J, Harrington L. Enforced telomere elongation increases thesensitivity of human tumour cells to ionizing radiation[J]. DNARepair(Amst), 2015, 25: 54-9. |

| [23] | Harrington L. Haploinsufficiency and telomere lengthhomeostasis[J]. Mutat Res, 2012, 730(1-2): 37-42. |

2015, Vol. 42

2015, Vol. 42