Efficacy and Safety of PD-1 Inhibitor Combined with Anlotinib on Advanced Neuroendocrine Carcinoma

-

摘要:目的

分析程序性死亡受体-1(PD-1)抑制剂联合安罗替尼治疗晚期神经内分泌癌的疗效及安全性。

方法收集郑州大学第一附属医院经一线标准化疗失败、应用PD-1抑制剂联合安罗替尼治疗的晚期神经内分泌癌患者资料。

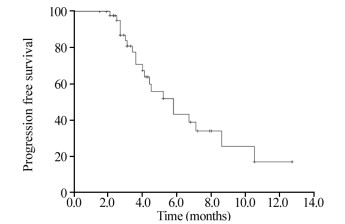

结果共纳入45例患者,男性24例,女性21例;年龄42~84岁,中位年龄57岁。肿瘤原发部位:肺23例(51.1%)、食管8例(17.8%)、胰腺和直肠各7例(15.6%)。18例(40.0%)患者既往一线和二线治疗失败,27例(60.0%)患者三线及以上治疗失败。所有患者接受2~15周期的治疗,3例因疾病进展死亡,总体客观缓解率为11.1%,疾病控制率为53.5%,中位无进展生存期为5.8月,10月无进展生存率为25.5%。不良反应主要为1~2级骨髓抑制和消化道反应。

结论PD-1联合安罗替尼治疗晚期神经内分泌癌疗效较好,耐受性好,可作为晚期神经内分泌癌标准一线治疗失败后的选择。

Abstract:ObjectiveTo analyze the efficacy and safety of PD-1 inhibitor combined with anlotinib on advanced neuroendocrine carcinoma.

MethodsWe collected the data of patients with advanced neuroendocrine carcinoma who had failed the first-line standard chemotherapy and treated with PD-1 inhibitor combined with anlotinib from the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University.

ResultsA total of 45 patients, including 24 males and 21 females, were included. The median age was 57 years old. The primary tumor sites were lung (23 cases, 51.1%), esophagus (8 cases, 17.8%), pancreas (7 cases, 15.6%) and rectum (7 cases, 15.6%). Eighteen cases (40%) had failed the first- and second-line treatments, and 27 cases (60%) had failed the third-line and above treatments. All patients received 2-15 cycles of treatment, 3 cases died due to disease progression, overall objective response rate was 11.1%, disease control rate was 53.5%, median progression-free survival was 5.8 months, and 10-month progression-free survival rate was 25.5%. Adverse events were mainly grade 1-2 myelosuppression and digestive tract reactions.

ConclusionPD-1 combined with anlotinib show better efficacy and good tolerance on advanced neuroendocrine carcinoma. It can be used as a choice after the failure of standard first-line treatment of advanced neuroendocrine carcinoma.

-

Key words:

- Immune checkpoint inhibitor /

- PD-1 /

- Anlotinib /

- Neuroendocrine carcinoma

-

0 引言

多形性胶质母细胞瘤(glioblastoma multiforme, GBM)是成人最常见的恶性原发性脑肿瘤之一。目前主要治疗手段包括手术切除联合放疗,但疗效不佳,中位生存期仅12~15月[1]。通过手术获得的肿瘤组织的组织学检查是目前确定性诊断的必要条件。尽管神经系统影像学检查可以提供GBM诊断价值,但对与GBM具有相似的影像学特征的其他脑病变诊断价值不大。因此,在组织学结果不确定或手术禁忌的情况下,筛选GBM分子标志物将为其诊断提供一定帮助。目前已经发现一些GBM中潜在的生物标志物,如PTEN[2]、IDH1[3]、TP53[4]。

本研究利用生物信息学方法对基因芯片GSE7696进行分析来获得差异表达基因(differentially expressed genes, DEGs),并对差异基因进行聚类分析和功能富集分析,同时构建蛋白互作(protein-protein interaction, PPI)网络来筛选核心基因,最后通过TCGA肿瘤数据库GBM全基因组表达谱数据,对核心基因的表达水平进行验证,以提供GBM更多可能的潜在诊断和治疗的分子靶标。

1 材料与方法

1.1 芯片数据

从GEO(gene expression omnibus, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/)中下载编号为GSE7696[5]的基因芯片,该芯片共有84例样本,包括4例正常脑组织样本(对照组)和80例GBM组织样本(实验组),比较实验组和对照组之间基因表达谱的差异情况。该芯片的平台信息:GPL570(HG-U133 Plus 2.0,Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array)。芯片的探针注释信息来自Affymetrix公司,包含54 675条探针信息。芯片表达谱分析方法利用R软件(https://www.r-project.org/)。

1.2 样本的预处理及聚类分析

从GEO数据库下载原始CEL文件,利用R软件读取原始文件后,使用Affy包中的RMA算法标准化数据后得到基因的表达矩阵,计算样本之间的Pearson相关系数,对所有样本进行聚类分析,剔除离群样本。

1.3 差异表达基因分析

将预处理后得到的基因表达矩阵文件用R软件读入,利用R软件中limma包[6]对80例GBM组织样本和4例正常脑组织样本进行差异表达分析,并且应用贝叶斯检验方法进行多重检验校正。差异基因筛选标准为P < 0.05,基因表达值倍数变化(fold change, FC)≥2或≤-2。

1.4 GO功能注释、KEGG信号富集以及通路网络构建

采用DAVID在线分析平台[7](https://david.ncifcrf.gov/)对差异基因在基因本体(gene ontology, GO)中注释其参与的生物学过程(biological process, BP),并进行京都基因与基因组百科全书(Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes, KEGG)通路分析。采用Cytoscape软件对富集到的所有信号通路进行网络构建。

1.5 蛋白互作网络构建及核心蛋白筛选

利用String蛋白互作数据库[8](the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes, STRING, http://string-db.org/)分析GBM组织和正常脑组织差异基因之间的蛋白互作关系,构建蛋白质互作网络,以综合评分(combination score)大于0.4为阈值条件。将STRING中所得蛋白互作网络数据导入Cytoscape软件[9],运用其网络分析(network analyzer)插件计算节点的边(Degree, 即互作连线的数量)筛选网络中心节点(Hub Node)。中心节点对应的蛋白质为具有重要生理调节功能的核心蛋白质(基因)[10]。

1.6 核心蛋白(基因)的验证

利用TCGA肿瘤数据库(The Cancer Genome Atlas Database, https://cancergenome.nih.gov/)获取169例GBM样本和5例正常脑组织样本全基因组表达谱数据,对PPI网络的核心基因进行进一步验证。

1.7 统计学方法

采用SPSS19.0统计软件。两组比较采用t检验,P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果

2.1 样本聚类分析

Pearson相关分析结果显示80例GBM组织样本和4例正常脑组织样本聚类良好,无离群样本,84例样本均可用于下一步分析,见图 1。

2.2 差异表达基因

以P < 0.05,基因表达值倍数变化≥2或≤-2为筛选条件。GBM组织和正常脑组织DEGs一共2 142个,其中上调基因968个,下调基因1 174个,见图 2。差异基因基本能够区分肿瘤组织样本和正常组织样本。

2.3 差异表达基因生物学功能注释

GO功能注释显示,GBM中差异表达基因富集到的生物学过程(biological process, BP)中富集度最高的20条,见图 3A。其中与GBM密切相关程度最高的3个生物学过程是突触传递(synaptic transmission)、有丝分裂细胞周期(mitotic cell cycle)、细胞分裂(cell division)。图 3A中每一条横柱代表一个生物学过程,横柱的长度代表富集到的差异基因数目,颜色越红表示P值越小,越具有统计学意义,下同。

2.4 差异表达基因KEGG信号通路及信号通路网络(pathway network)

利用DAVID在线富集工具将差异基因进行KEGG信号通路富集,图 3B显示富集度最高的20条通路。其中在GBM中明显富集且研究较多的3条信号通路有细胞周期(cell cycle)、MAPK信号通路(MAPK signaling pathway)以及PI3K-Akt信号通路(PI3K-Akt signaling pathway)。信号通路网络图(图 3C)显示MAPK信号通路、凋亡(apoptosis)、细胞周期以及P53信号通路(P53 signaling pathway)在通路网络中处于核心地位,说明他们在GBM的发生发展中起到极其重要的作用。图 3C中点的大小代表degree值,点越大代表通路越核心;颜色反映了通路中差异表达基因的情况,红色代表差异基因全部上调,蓝色代表下调,黄色代表既有上调又有下调。带箭头的实线表示两个信号通路之间的上下游关系,箭头起始端为上游的信号通路,箭头指向端为下游的信号通路。

2.5 通过Cytoscape软件构建的蛋白互作网络

网络分析显示,根据每个基因的节点数目排序,节点数目最多的基因,代表在整个PPI网络中所起的作用越大,即最相关的核心基因,有CDK1、KIF2C、BIRC5、CDC20、KIF11、CENPA、KIF20A、TOP2A、NDC80等9个核心基因,见图 4。这9个核心基因中全部在GBM中表达升高,差异有统计学意义,见表 1。

表 1 GBM基因芯片数据GSE7696中9个核心基因表达情况Table 1 Detailed information of the nine hub genes in GSE7696 gene chip

2.6 核心基因TCGA肿瘤数据库验证

从TCGA肿瘤数据库获取169例GBM样本和5例正常脑组织样本全基因组表达谱数据,比较这9个核心基因在GBM和正常组织中的转录水平,相对于正常组织,9个基因在GBM样本中表达明显升高,差异有统计学意义(P < 0.001),见图 5(略)。

3 讨论

目前基因芯片在疾病的诊断,特别是肿瘤和正常组织对比、肿瘤组织来源的鉴别等方面具有重要作用。它可用于肿瘤基因表达检测,寻找新基因,为寻找肿瘤的分子靶标提供了一个重要手段。

本研究从GEO芯片数据库获取了美国Affymatrix公司全基因组表达谱芯片,包括80例GBM组织和4例正常的脑组织样本,进行深入分析,以Fold Change绝对值≥2和差异显著性指标P < 0.05为条件,我们获得差异表达基因的数目为2 142个,其中上调968个,下调1 174个。这一结果提示在GBM发生发展的过程中,多种肿瘤相关的基因表达异常或者肿瘤抑制基因表达失活,说明GBM是由多个分子生物学调节异常共同导致。

为了探究这些调节异常基因在GBM中所起的生物学作用,我们将获得的2 142个差异基因进行GO功能注释,结果发现这些基因群主要参与细胞周期、细胞增殖、信号转导以及小分子物质代谢过程,由此说明这些生物学过程的调节异常是导致GBM发生发展的重要因素。同时,为了探究这些基因群所参与的信号通路过程,我们将差异基因进行了KEGG信号通路富集分析,同样发现细胞周期的异常调节在GBM中占有重要地位,其他明显富集到的信号通路有PI3K-AKT信号通路,肿瘤相关信号通路、钙离子信号通路以及MAPK信号通路。对富集到的信号通路进行网络分析后发现,MAPK信号通路处于通路网络的核心,由此说明GBM的发生与该信号通路密切相关。MAPK又称丝裂原活化蛋白激酶,是信号从细胞表面转导到细胞核内部的重要传递者,许多肿瘤的发生和发展都与MAPK信号通路的异常调节有关[11]。以上结果对于研究GBM的生物学发生过程具有很好的提示作用,有待进一步验证。

在9个核心基因中,与细胞周期调节有关的有CDK1和CDC20。CDK1又称细胞周期蛋白依赖性激酶1,是一种高度保守的蛋白质,起到丝氨酸/苏氨酸激酶的作用,是细胞周期调控的关键参与者。CDK1的过度表达与多种肿瘤细胞的增殖密切相关[12]。CDC20又称细胞分裂周期蛋白20,通过与其他几种蛋白质相互作用从而在细胞周期的多个点上起到调节作用[13]。

与细胞分裂有关的基因有KIF2C、KIF11、CENPA、KIF20A、TOP2A、NDC80。KIF2C属于驱动蛋白样蛋白家族的成员,该家族的大多数蛋白质是微管依赖的分子马达,在细胞分裂期间运输细胞器中的细胞器并移动染色体。最新的研究表明,沉默KIF11可以导致染色体的不稳定从而促进肿瘤的发生[14]。CENPA是修饰的核小体或核小体样结构的组成部分,其含有靶向着丝粒所需的组蛋白H3相关蛋白结构域,在细胞的有丝分裂中发挥重要作用,研究表明CENPA是乳腺癌潜在的预后生物标志物,其表达增加与乳腺癌的不良预后有关[15]。KIF20A过表达与宫颈癌患者进展和不良预后有关[16],并且,研究发现KIF20A在神经胶质瘤组织中高表达并且提示预后不良[17]。TOP2A基因编码DNA拓扑异构酶,是一种控制和改变转录过程中DNA拓扑状态的酶,在乳腺癌[18]、神经母细胞瘤[19]、肺癌[20]等肿瘤中高表达,并且促进肿瘤细胞的增殖和迁移。NDC80在细胞有丝分裂的过程中主要参与染色体的正确分离的调控,有研究发现过表达NDC80后能够明显促进结肠癌细胞的增殖和迁移[21]。

BIRC5又称survivin蛋白或者存活蛋白,凋亡抑制剂家族的成员。survivin蛋白抑制半胱天冬酶活性的作用,从而负性调控导致凋亡。抑制survivin蛋白导致细胞凋亡增加和肿瘤生长减少[22]。数据表明survivin蛋白可能作为癌症治疗的新靶标。最近研究发现survivin蛋白的核表达是GBM患者预后不良的一个因素,survivin蛋白亚细胞定位可以帮助预测用标准方案治疗的GBM患者的总生存期[23]。

综上,应用基因表达谱芯片可以筛选GBM相关基因及信号通路,是否是GBM特异的敏感基因需要更多病例验证以及细胞实验的进一步研究,希望从中能筛选出有助于GBM早期诊断和治疗的分子标志物或基因治疗靶点。

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.作者贡献余旭旭:数据收集、随访、统计分析、论文撰写李向柯、杨闽洁:论文修改陈钟、毛迎港:数据收集宋丽杰:课题设计、经费支持 -

表 1 45例神经内分泌癌患者临床病理特征

Table 1 Clinicopathological characteristics of 45 patients with neuroendocrine carcinoma

表 2 免疫检查点抑制剂联合靶向治疗不良反应(n(%))

Table 2 Adverse reactions of immune checkpoint inhibitors combined with targeted therapy (n(%))

-

[1] Klöppel G. Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Dichotomy, Origin and Classifications[J]. Visc Med, 2017, 33(5): 324-330. doi: 10.1159/000481390

[2] Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, et al. One hundred years after "carcinoid": epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35, 825 cases in the United States[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2008, 26(18): 3063-3072. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4377

[3] 翟雪佳, 于顺利, 马怡晖, 等. 神经内分泌瘤488例临床病理特征及预后分析[J]. 中华医学杂志, 2019, 99(32): 2527-2531. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0376-2491.2019.32.012 Zhai XJ, Yu XL, Ma YH, et al. Clinicopathological features and prognosis of 488 patients with neuroendocrine tumors[J]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi, 2019, 99(32): 2527-2531 doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0376-2491.2019.32.012

[4] Klimstra DS, Modlin IR, Coppola D, et al. The pathologic classification of neuroendocrine tumors: a review of nomenclature, grading, and staging systems[J]. Pancreas, 2010, 39(6): 707-712. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181ec124e

[5] Saeger W, Schnabel PA, Komminoth P. Grading of neuroendocrine tumors[J]. Pathologe, 2016, 37(4): 304-313. doi: 10.1007/s00292-016-0186-4

[6] Shah MH, Goldner WS, Halfdanarson TR, et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Neuroendocrine and Adrenal Tumors, Version 2.2018[J]. J Natl Compr Canc Netw, 2018, 16(6): 693-702. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2018.0056

[7] Travis WD, Brambilla E, Burke AP, et al. Introduction to The 2015 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus, and Heart[J]. J Thorac Oncol, 2015, 10(9): 1240-1242. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000663

[8] 2013年中国胃肠胰神经内分泌肿瘤病理诊断共识专家组. 中国胃肠胰神经内分泌肿瘤病理诊断共识(2013版)[J]. 中华病理学杂志, 2013, 42(10): 691-694. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-5807.2013.10.011 Chinese Expert Group on Pathological Diagnosis of Gastrointestinal Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Chinese Consensus on Pathological Diagnosis of Gastrointestinal Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors (2013 Edition)[J]. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi, 2013, 42(10): 691-694. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-5807.2013.10.011

[9] Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1)[J]. Eur J Cancer, 2009, 45(2): 228-247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026

[10] Dasari A, Shen C, Halperin D, et al. Trends in the Incidence, Prevalence, and Survival Outcomes in Patients With Neuroendocrine Tumors in the United States[J]. JAMA Oncol, 2017, 3(10): 1335-1342. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0589

[11] Dasari A, Mehta K, Byers LA, et al. Comparative study of lung and extrapulmonary poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas: A SEER database analysis of 162, 983 cases[J]. Cancer, 2018, 124(4): 807-815. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31124

[12] 张剑, 臧凤琳, 张家丽, 等. 分化差的胃神经内分泌肿瘤预后分析[J]. 肿瘤防治研究, 2019, 46 (5): 447-451. doi: 10.3971/j.issn.1000-8578.2019.18.1770 Zhang J, Zang FL, Zhang J, et al. [ZHANG Prognosis of Poorly-differentiated Gastric Neuroendocrine Neoplasm[J]. Zhong Liu Fang Zhi Yan Jiu, 2019, 46(5): 447-451. doi: 10.3971/j.issn.1000-8578.2019.18.1770

[13] Antonia SJ, López-Martin JA, Bendell J, et al. Nivolumab alone and nivolumab plus ipilimumab in recurrent small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 032): a multicentre, open-label, phase 1/2 trial[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2016, 17(7): 883-895. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30098-5

[14] Chung HC, Piha-Paul SA, Lopez-Martin J, et al. Pembrolizumab After Two or More Lines of Previous Therapy in Patients With Recurrent or Metastatic SCLC: Results From the KEYNOTE-028 and KEYNOTE-158 Studies[J]. J Thorac Oncol, 2020, 15(4): 618-627. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.12.109

[15] Mansfield AS, Każarnowicz A, Karaseva N, et al. Safety and patient-reported outcomes of atezolizumab, carboplatin, and etoposide in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (IMpower133): a randomized phaseⅠ/Ⅲ trial[J]. Ann Oncol, 2020, 31(2): 310-317. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2019.10.021

[16] Paz-Ares L, Dvorkin M, Chen Y, et al. Durvalumab plus platinum-etoposide versus platinum-etoposide in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (CASPIAN): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial[J]. Lancet, 2019, 394(10212): 1929-1939. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32222-6

[17] Han B, Li K, Wang Q, et al. Effect of Anlotinib as a Third-Line or Further Treatment on Overall Survival of Patients With Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: The ALTER 0303 Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trial[J]. JAMA Oncol, 2018, 4(11): 1569-1575. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.3039

[18] Chi Y, Fang Z, Hong X, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Anlotinib, a Multikinase Angiogenesis Inhibitor, in Patients with Refractory Metastatic Soft-Tissue Sarcoma[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2018, 24(21): 5233-5238. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-3766

[19] Sun Y, Du F, Gao M, et al. Anlotinib for the Treatment of Patients with Locally Advanced or Metastatic Medullary Thyroid Cancer[J]. Thyroid, 2018, 28(11): 1455-1461. doi: 10.1089/thy.2018.0022

[20] Syed YY. Anlotinib: First Global Approval[J]. Drugs, 2018, 78(10): 1057-1062. doi: 10.1007/s40265-018-0939-x

[21] Elamin YY, Rafee S, Toomey S, et al. Immune effects of bevacizumab: killing two birds with one stone[J]. Cancer Microenviron, 2015, 8(1): 15-21. doi: 10.1007/s12307-014-0160-8

[22] Heine A, Held SA, Bringmann A, et al. Immunomodulatory effects of anti-angiogenic drugs[J]. Leukemia, 2011, 25(6): 899-905. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.24

[23] Kerr KM, Nicolson MC. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, PD-L1, and the Pathologist[J]. Arch Pathol Lab Med, 2016, 140(3): 249-254. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2015-0303-SA

[24] Kerr KM, Hirsch FR. Programmed Death Ligand-1 Immunohistochemistry: Friend or Foe?[J]. Arch Pathol Lab Med, 2016, 140(4): 326-331. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2015-0522-SA

[25] Cheng Y, Wang Q, Li K, et al. OA13.03 Anlotinib as Third-Line or Further-Line Treatment in Relapsed SCLC: A Multicentre, Randomized, Double-Blind Phase 2 Trial[J]. J Thorac Oncol, 2018, 13(10): S351-S352.

[26] Gao L, Yang X, Yi C, et al. Adverse Events of Concurrent Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Antiangiogenic Agents: A Systematic Review[J]. Front Pharmacol, 2019, 10: 1173. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01173

[27] Bonanno L, Pavan A, Dieci MV, et al. The role of immune microenvironment in small-cell lung cancer: Distribution of PD-L1 expression and prognostic role of FOXP3-positive tumour infiltrating lymphocytes[J]. Eur J Cancer, 2018, 101: 191-200. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.06.023

[28] Subbiah V, Solit DB, Chan TA, et al. The FDA approval of pembrolizumab for adult and pediatric patients with tumor mutational burden (TMB) ≥10: a decision centered on empowering patients and their physicians[J]. Ann Oncol, 2020, 31(9): 1115-1118. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.07.002

[29] Peifer M, Fernández-Cuesta L, Sos ML, et al. Integrative genome analyses identify key somatic driver mutations of small-cell lung cancer[J]. Nat Genet, 2012, 44(10): 1104-1110. doi: 10.1038/ng.2396

[30] Hellmann MD, Callahan MK, Awad MM, et al. Tumor Mutational Burden and Efficacy of Nivolumab Monotherapy and in Combination with Ipilimumab in Small-Cell Lung Cancer[J]. Cancer Cell, 2018, 33(5): 853-861. e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.04.001

[31] Ricciuti B, Kravets S, Dahlberg SE, et al. Use of targeted next generation sequencing to characterize tumor mutational burden and efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibition in small cell lung cancer[J]. J Immunother Cancer, 2019, 7(1): 87. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0572-6

-

期刊类型引用(5)

1. 安俊达,李玉双. 基于超声图像评估甲状腺和乳腺病变的通用计算方法. 燕山大学学报. 2024(01): 86-94 .  百度学术

百度学术

2. 杨茜雯,宋博,高婷婷,薛无瑕,李立坤,纪永章. 2021—2022年某三甲医院体检人群重要异常结果分布特征分析. 健康体检与管理. 2024(02): 174-177+202 .  百度学术

百度学术

3. 杨倩倩,夏源,张云飞,杨桂云,郭文佳,张秀华. 基于列线图的女性乳腺癌患者再发第二原发性甲状腺癌风险预测模型的构建和验证. 中国医药导报. 2024(24): 117-124 .  百度学术

百度学术

4. 阙厦丹,陈敦雁. 乳腺良性肿瘤和恶性肿瘤与自身免疫性甲状腺疾病的关系. 慢性病学杂志. 2023(05): 755-757 .  百度学术

百度学术

5. 王婷. 中西医结合治疗乳腺癌术后甲状腺结节的临床疗效. 世界复合医学. 2022(04): 109-111+116 .  百度学术

百度学术

其他类型引用(1)

下载:

下载: