Effect of LSD1 on Proliferation and Metastasis of Ovarian Cancer Cells by Regulating Foxo3a

-

摘要:目的

探讨赖氨酸特异性去甲基化酶1(LSD1)如何通过调控转录因子Foxo3a影响卵巢癌细胞增殖和迁移。

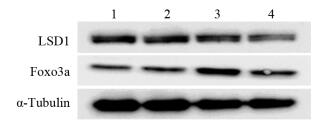

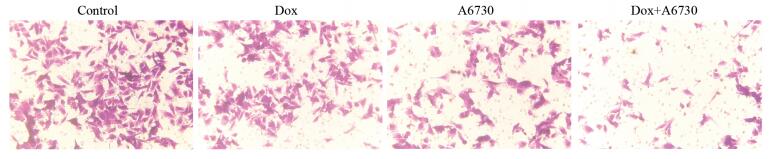

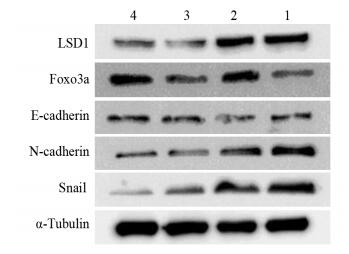

方法实验组A:取诱导型稳定干扰LSD1表达的人卵巢癌HO8910细胞株(HO8910-LSD1-shRNA)分为观察组和对照组,蛋白质印迹法检测LSD1和Foxo3a蛋白表达水平;实验组B:将HO8910-LSD1-shRNA细胞分为对照组、Dox组、A6730组和联合组,CCK-8检测各组细胞增殖抑制率,Transwell小室检测各组细胞迁移能力,蛋白质印迹法检测EMT相关蛋白表达。

结果在实验组A中,观察组LSD1蛋白水平随Dox浓度增加逐渐下降,而Foxo3a蛋白表达水平逐渐升高。在实验组B中,与对照组比较,Dox组、A6730组和联合组细胞增殖抑制率、细胞迁移率均显著减少(均P < 0.05);联合组较Dox组,细胞增殖抑制率、细胞迁移率均显著减少(均P < 0.05)。与对照组比较,Dox组、A6730组和联合组E-cadherin蛋白表达水平明显升高,而N-cadherin和Snail蛋白水平降低。与Dox组和A6730组比较,联合组E-cadherin表达量增加,而N-cadherin及Snail表达量减少。

结论敲低LSD1基因表达可以上调转录因子Foxo3a蛋白水平,从而抑制卵巢癌HO8910细胞增殖和转移。

Abstract:ObjectiveTo investigate the effects of lysine-specific demethylation 1 (LSD1) on the proliferation and metastasis of ovarian cancer cells by regulating Foxo3a.

MethodsIn test group A, the human ovarian cancer cell line HO8910 (HO8910-LSD1-shRNA) with inducible stable knockdown of LSD1 expressions were divided into the observation groups and the control group. The expression levels of LSD1 and Foxo3a proteins were detected by Western blot. Then in test group B, the HO8910-LSD1-shRNA cells were divided into Control group, Dox group, A6730 group and Dox+A6730 group. The cell proliferation inhibition rate of each group was detected by CCK-8, and the metastasis levels of each group were detected by Transwell assay. The EMT-related proteins expressions were detected by Western blot.

ResultsIn test group A, with the increasing Dox concentration in the observation groups, the expression level of LSD1 protein was gradually decreased, while the expression level of Foxo3a protein was gradually increased. In test group B, compared with the control group, the proliferation inhibition rates, cell migration rates of Dox group, A6730 group and combination group were significantly lower (P < 0.05); cell proliferation inhibition rate and cell migration rate of the Dox+A6730 group were significantly lower than those of Dox group (both P < 0.05). Compared with the control group, the expression levels of E-cadherin protein in Dox group, A6730 group and combination group were increased significantly, while the levels of N-cadherin and Snail protein were decreased. Compared with Dox and A6730 groups, the expression of E-cadherin was increased, while the expression of N-cadherin and Snail were decreased in the combination group.

ConclusionKnocking down the expression of LSD1 gene could upregulate the transcription factor Foxo3a protein level, thereby inhibiting the proliferation metastasis of ovarian cancer HO8910 cells.

-

Key words:

- Ovarian cancer /

- Proliferation /

- Metastasis /

- LSD1 /

- Foxo3a

-

0 引言

1960年以前,截肢一直是恶性骨肿瘤的标准治疗[1]。随着内科肿瘤学、外科技术和重建方法的进步,保肢手术已逐渐成为主流,大约90%的原发恶性骨肿瘤患者接受保肢治疗[2-3]。下肢肿瘤切除后骨缺损的重建方法很多,包括异体骨、自体腓骨移植、自体骨灭活再植等,其中肿瘤型人工关节已成为目前应用最为广泛的方法。随着肿瘤患者存活时间的延长,人工关节术后假体失败已成为不得不面对的问题[4-5]。

据文献报道,无菌性松动占所有假体失败的19.1%,是第二常见失败类型[5]。肿瘤型假体的无菌性松动往往因为残余骨量少、质量差,最终不得不采用更大的假体(如全股骨置换)来进行重建,有些患者不得不截肢[6]。因此,肿瘤型假体无菌性松动的翻修充满挑战。

GMRS(global modular replacement system)肿瘤型人工关节(GMRSTM, Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI, USA)提供了一套骨肿瘤骨缺损重建方案,包括直柄、弯柄和长弯柄3种类型,每种类型都可搭配多孔涂层假体,而多孔涂层是连接假体柄的一段4 cm的结构,有助于自身骨质的长入,起到生物愈合的作用。本研究采用含有多孔涂层的大直径短柄GMRS肿瘤型人工关节(直径13 mm或15 mm,长度12.7 cm)用于治疗肿瘤型人工假体出现的无菌性松动。据检索,文献中尚无GMRS肿瘤型人工关节用于翻修的报道。本试验拟研究无菌性松动后采用GMRS假体置换术的假体累积存活率和患者的功能预后。

1 资料与方法

1.1 纳入与排除标准

纳入标准:(1)2009年1月至2012年12月,于北京积水潭医院骨肿瘤科因肿瘤型人工假体松动就诊并接受治疗的患者;(2)通过术前影像学检查,包括下肢的X线和CT扫描来评估,患侧骨质长度≥17 cm,剩余骨段皮质骨厚度≥1 mm;(3)术前血常规、血沉和C反应蛋白均正常,无活动性局部或全身感染;(4)双下肢全长差≤3 cm。排除标准:(1)患者存在局部肿瘤复发或者远处转移病灶;(2)影像学评估提示残余骨质长度 < 17 cm或厚度 < 1 mm;(3)患侧肢体曾接受过放疗。

1.2 一般资料

本研究共纳入16例患者,其中男9例、女7例,年龄14~55岁,平均28岁。原发肿瘤包括经典型骨肉瘤7例,骨巨细胞瘤6例,软骨肉瘤、软骨母细胞瘤及上皮样血管内皮瘤各1例。原发肿瘤位于股骨远端10例,胫骨近端4例,股骨近端2例。初次置换关节均为国产关节,除2例行股骨近端置换术外,8例为旋转铰链假体,6例为限制铰链假体。

1.3 手术方法

翻修手术包括两个步骤:第一步取出松动的假体,第二步置入新的假体。假体的各部分组件均需取出,包括没有出现松动的部分。采用骨水泥取出器械,尽量取出第一次假体置换时的骨水泥。器械包括各种尺寸的角刀、普通骨刀、超声骨刀、高速磨钻以及一次性冲洗枪。骨水泥取出后,采用扩髓器扩髓,有效长度残余皮质骨的厚度≥1 mm,以支撑假体柄。GMRS假体在假体柄体连接部分提供了一个多孔涂层结构,在这个区域,需要修理自体皮质骨做骨桥处理,见图 1A。具备多孔涂层结构的假体柄长度为4 cm,相应的皮质骨骨桥也设计为大约4 cm,需尽量保留该部分皮质骨的肌肉附丽和骨膜,以保证血液供应。在自体皮质带之间植入同种异体骨,并采用钢丝进行固定,见图 1B。假体柄均采用骨水泥进行固定,其余操作同常规人工关节置换。

![]() 图 1 术中自体皮质骨骨桥的处理Figure 1 Management of autogenous cortical bone bridge in operationA: the repair of the cortical bone of the distal femur, to form a bridge structure, with care to preserve the muscle attachments and periosteum surrounding the bridge; B: allogeneic bone was implanted between the gaps of the autogenous bone bridge and then fixed with steel wire.

图 1 术中自体皮质骨骨桥的处理Figure 1 Management of autogenous cortical bone bridge in operationA: the repair of the cortical bone of the distal femur, to form a bridge structure, with care to preserve the muscle attachments and periosteum surrounding the bridge; B: allogeneic bone was implanted between the gaps of the autogenous bone bridge and then fixed with steel wire.1.4 康复与随访

鼓励患者在术后第二天进行股四头肌锻炼。术后8~10周,患者可在双拐辅助下行走,患肢可负重5~10公斤,至12周左右完全负重。术后第1年内,每3个月进行1次随访,然后每6个月进行1次,连续两年,此后每年复查1次。

1.5 评价指标

每次随访,患者都要接受体格检查和影像学评估。影像学检查主要包括肿瘤和假体相关并发症的监测。多孔涂层骨长入的评估采用末次随访的X线片,按照Coathup等[7]描述的方法进行。多孔涂层骨长入部分分为4个区域,包括前后位片的内侧和外侧,侧位片的前面和后面。评分从0~4分不等,任何1个区域,如果符合多孔涂层骨长入部分骨桥厚度 > 5 mm且长度 > 2 cm,即可得到1分。4分代表多孔涂层在所有4个区域都有符合条件的骨长入。MSTS功能评分评估患者的肢体功能[8]。

1.6 统计学方法

采用SPSS25.0软件进行统计分析,随访时间以平均值、中位数、标准差和范围表示。假体5年和8年存活率采用Kaplan-Meier方法进行计算。每次随访记录假体是否出现无菌性松动。配对t检验比较初次人工关节置换与翻修后GMRS人工关节无菌性松动的时间。Kaplan-Meier法计算人工关节无菌性松动生存时间。检验水准为α=0.05。

2 结果

2.1 翻修假体的生存率

所有患者都未失随访,未出现局部复发或全身转移。至末次随访,所有患者均无瘤存活。翻修假体的5年和8年累积生存率均为94%。有2例假体失败,其中1例24岁的患者诊断为股骨远端经典型骨肉瘤,接受了新辅助化疗、肿瘤切除和假体置换、以及辅助化疗。术后51个月人工关节出现无菌性松动,随后接受GMRS假体翻修,术后28个月被诊断为假体感染,手术取出原假体,未出现假体松动;1例股骨远端软骨肉瘤的患者在翻修术后118个月被再次诊断为无菌性松动。由于患者有疼痛症状,再次翻修,仍然采用GMRS人工假体。其余14例未出现假体失败的患者平均随访时间和中位随访时间分别为90和92个月(52~118个月)。

2.2 无菌性松动的评价

第1次假体置换和翻修手术之间的平均间隔和中位间隔分别为81和73个月(27~187个月)。除1例发生感染外,其余15例均通过随访时X线检查评价无菌性松动情况。其中1例患者再次接受了翻修手术,整体复发性无菌性松动率仅为6.7%(1/15);其余14例,中位随访92个月(52~118个月),无患者出现无菌性松动。85.7%(12/14)患者翻修后未出现无菌性松动的生存时间(90.6±19.3个月)明显长于初次治疗假体生存时间(43.4±29.7个月),差异有统计学意义(t=4.297, P=0.001)。据末次随访X线评估,平均骨长入评分3分(0~4),见图 2。14例患者中7例(50.0%)评分4分,3例(21.4%)评分3分,2例(14.3%)评分2分,1分和0分患者各1例(7.1%)。

![]() 图 2 一例出现再次松动患者的影像学资料Figure 2 Imaging data of one patient with repeated aseptic looseningA: longitudinal position of the prosthesis stem before the revision; B-C: three months after revision, shorter and thicker stems were selected; D-E: 33 months after revision, the porous coated bone grew into part of the bridge and healed well; F-G: 118 months after revision, repeated aseptic loosening; H: immediate X-ray image after repeated revision, the porous coated bone bridge technique was used again; I: X-ray image 22 months after repeated revision, no sign of aseptic loosening.

图 2 一例出现再次松动患者的影像学资料Figure 2 Imaging data of one patient with repeated aseptic looseningA: longitudinal position of the prosthesis stem before the revision; B-C: three months after revision, shorter and thicker stems were selected; D-E: 33 months after revision, the porous coated bone grew into part of the bridge and healed well; F-G: 118 months after revision, repeated aseptic loosening; H: immediate X-ray image after repeated revision, the porous coated bone bridge technique was used again; I: X-ray image 22 months after repeated revision, no sign of aseptic loosening.2.3 翻修假体的肢体功能

除1例感染及1例再次翻修患者,其余14例患者均接受了MSTS功能评分。翻修术后中位随访时间90个月(52~118个月),平均MSTS功能评分为27.7(24~30)。

3 讨论

一直以来,肿瘤型人工假体在骨肿瘤切除后骨缺损的重建中发挥着重要的作用。尽管工业材料的发展和模块化设计的创新,肿瘤型人工假体已获得很大进步,但假体置换术后失败仍时常发生。2010年,Henderson等提出了肿瘤假体失败的5种类型,其中无菌性松动被定义为2型。下肢无菌性松动失败率为7.7%~18.8%[9-13],远高于整体病例无菌性松动的失率(4.7%)[4]。虽然有很多关于恶性骨肿瘤肿瘤型人工关节治疗的数据报道,但很少有无菌性松动或再次接受翻修假体治疗的相关研究[14-16]。本研究回顾分析了肿瘤型人工假体翻修后的数据,发现翻修假体的5年和8年的累计生存率均为94%。16例患者仅1例再次出现无菌性松动,反复无菌性松动率降至6.3%(1/16)。

本研究存在几个局限性;首先,本研究为回顾性研究。虽然所有患者均未失随访,但部分患者未能进行规律的定期随访,因此无法了解无菌性松动发生的自然病程;其次,本研究仅有16例患者数据,对于翻修假体的评估需要更多的病例数,包括采用多中心前瞻性临床研究来验证其有效性,但本组病例数据都来自同一个中心,适应证(只有无菌性松动)和解剖部位(下肢)严格限制,肿瘤假体类型和手术技巧也比较统一,有助于了解符合这一特点的病例数据特点;第三,未采用其他假体的翻修病例作为对照组(例如选择更长的假体柄或者生物柄假体),一定程度上削弱了本研究的循证医学证据级别。

目前,导致假体无菌性松动的因素尚未明确。Kawai等[17]和Unwin等[18]提出采用骨切除长度来预测无菌性松动的发生。对于股骨远端和胫骨近端,切除越长,无菌性松动的发生的风险越高,然而,并未在股骨近端观察到该特点。Bergin等提出只有骨干比才是无菌性松动的一个独立危险因素[19],采用粗假体柄(φ14.5 mm)患者出现无菌性松动的生存时间要明显长于细柄患者(φ10.7 mm)。我们的经验类似,支持采用粗柄假体(φ13 mm或15 mm)。Zimel等[14]报道了一种相对较短的假体柄CPS,经过90个月的中位随访,假体失败包括机械故障和深部感染,但未出现无菌性松动的病例。在另一篇报道中,术后6.3年的CPS无菌性松动失败率仅为3.8%[20]。膝关节周围非骨水泥型肿瘤假体的无菌性松动发生率仅为2%(2/99)[21],但其他并发症包括假体柄骨折和感染的发生率高于其他报道。

多孔涂层骨外桥接有望起到生物固定的效果,不仅可以分散假体周围宿主骨的应力,还通过封闭接合区防止磨损颗粒的渗入来防止骨溶解。Coathup等报道了股骨远端植入羟基磷灰石涂层的假体10年存活率为88.9%[7]。与没有多孔涂层骨外桥接的假体相比,带有多孔涂层的假体的生存率有增加的趋势。本研究中,皮质外骨长入平均得分为3,这可能有助于解释翻修后无菌性松动率发生较低的原因。该组翻修患者的术后肢体功能结果与上述文献报道相似。

总之,肿瘤型人工关节术后的无菌性松动再次翻修充满挑战。本研究报告了一种假体翻修方法,结果显示中长期疗效满意。假体翻修的核心是尽量保留宿主骨,早期应获得坚强固定,后期尽量实现生物固定。但由于本研究病例数量有限,未来期待前瞻性的研究获得更多数据支持。

-

表 1 四组卵巢癌细胞的生长抑制情况(x±s)

Table 1 Proliferation of ovarian cancer cells in four groups(x±s)

表 2 四组卵巢癌细胞的迁移情况(x±s)

Table 2 Metastasis of ovarian cancer cells in four groups (x±s)

-

[1] Maldonado L, Hoque MO. Epigenomics and ovarian carcinoma[J]. Biomark Med, 2010, 4(4): 543-70. doi: 10.2217/bmm.10.72

[2] Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, et al. Cancer statistics, 2010[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2010, 60(5): 277-300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073

[3] Cao C, Vasilatos SN, Bhargava R, et al. Functional interaction of histone deacetylase 5 (hdac5) and lysine-specific demethylase 1 (lsd1) promotes breast cancer progression[J]. Oncogene, 2017, 36(1): 133-45. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.186

[4] Amente S, Milazzo G, Sorrentino MC, et al. Lysine-specific demethylase (lsd1/kdm1a) and mycn cooperatively repress tumor suppressor genes in neuroblastoma J]. Oncotarget, 2015, 6(16): 14572-83. http://pubmedcentralcanada.ca/pmcc/articles/PMC4546488/

[5] Sakamoto A, Hino S, Nagaoka K, et al. Lysine demethylase lsd1 coordinates glycolytic and mitochondrial metabolism in hepatocellular carcinoma cells[J]. Cancer Res, 2015, 75(7): 1445-56. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1560

[6] Zhang X, Zhang X, Yu B, et al. Oncogene lsd1 is epigenetically suppressed by mir-137 overexpression in human non-small cell lung cancer [J]. Biochimie, 2017, 137: 12-9. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2017.02.010

[7] Kauffman EC, Robinson BD, Downes MJ, et al. Role of androgen receptor and associated lysine-demethylase coregulators, lsd1 and jmjd2a, in localized and advanced human bladder cancer[J]. Mol Carcinog, 2011, 50(12): 931-44. doi: 10.1002/mc.20758

[8] Mould DP, McGonagle AE, Wiseman DH, et al. Reversible inhibitors of lsd1 as therapeutic agents in acute myeloid leukemia: Clinical significance and progress to date[J]. Med Res Rev, 2015, 35(3): 586-618. doi: 10.1002/med.2015.35.issue-3

[9] Konovalov S, Garcia-bassets I. Analysis of the levels of lysine-specific demethylase 1 (lsd1) mrna in human ovarian tumors and the effects of chemical lsd1 inhibitors in ovarian cancer cell lines [J]. J Ovarian Res, 2013, 6(1): 75. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-6-75

[10] 刘秀文, 魏野, 李袁霞, 等.沉默LSD1基因的表达可抑制卵巢癌H0890细胞的增殖并诱导其凋亡[J].肿瘤, 2016, 36(5): 485-95. http://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?filename=zzll201605001&dbname=CJFD&dbcode=CJFQ Liu XW, Wei Y, Li YX, et al. LSD1 gene-silencing inhibits proliferation and promotes apoptosis of ovarian cancer H08910 cells[J]. Zhong Liu, 2016, 36(5): 485-95. http://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?filename=zzll201605001&dbname=CJFD&dbcode=CJFQ

[11] Lin H, Dai T, Xiong H, et al. Unregulated mir-96 induces cell proliferation in human breast cancer by downregulating transcriptional factor foxo3a[J]. PLoS One, 2010, 5(12): e15797. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21203424/

[12] Mandinova A, Lefort K, Tommasi di Vignano A, et al. The FoxO3a gene is a key negative target of canonical notch signalling in the keratinocyte UVB response[J]. EMBO J, 2008, 27(8): 1243-54. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.45

[13] Schulte JH, Lim S, Schramm A, et al. Lysine-specific demethy lase1 is strongly expressed in poorly differentiated neuroblastoma: implications for therapy[J]. Cancer Res, 2009, 65(5): 2065-71. http://cn.bing.com/academic/profile?id=f14e5d066d7cfffd2a36247f95dd323b&encoded=0&v=paper_preview&mkt=zh-cn

[14] Huang Y, Nayak S, Jankowitz R, et al. Epigenetics in breast cancer: What's new?[J]. Breast Cancer Res, 2011, 13(6): 225. doi: 10.1186/bcr2925

[15] Lv T, Yuan D, Miao X, et al. Over-expression of lsd1 promotes proliferation, migration and invasion in non-small cell lung cancer [J]. PLoS One, 2012, 7(4): e35065. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035065

[16] Katoh M, Igarashi M, Fukuda H, et al. Cancer genetics and genomics of human fox family genes[J]. Cancer Lett, 2013, 328(2): 198-206. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.09.017

[17] Boix L, López-Oliva JM, Rhodes AC, et al. Restoring mir122 in human stem-like hepatocarcinoma cells, prompts tumor dormancy through smad-independent tgf-β pathway[J]. Oncotarget, 2016, 7(44): 71309-29. http://pubmedcentralcanada.ca/pmcc/articles/PMC5342080/?report=reader

[18] Cheng CW, Chen PM, Hsien YH, et al. Foxo3a-mediated overexpression of microrna-622 suppresses tumor metastasis by repressing hypoxia-inducible factor-1α in erk-responsive lung cancer[J]. Oncotarget, 2015, 6(42): 44222-38. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26528854

[19] Yang XB, Zhao JJ, Huang CY, et al. Decreased expression of the foxo3a gene is associated with poor prognosis in primary gastric adenocarcinoma patients[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(10): e78158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078158

[20] Das TP, Suman S, Alatassi H, et al. Inhibition of akt promotes foxo3a-dependent apoptosis in prostate cancer[J]. Cell Death Dis, 2016, 7: e2111. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.403

[21] Kocak C, Kocak FE, Bayhan Z, et al. Value of immunohistochemical detection of foxo3a as a prognostic marker in human breast carcinoma[J]. Inter J Clin Expe Pathol, 2016, 9(10): 9938-50. http://www.researchgate.net/publication/309618777_Value_of_immunohistochemical_detection_of_FOXO3a_as_a_prognostic_marker_in_human_breast_carcinoma

[22] Obradorhevia A, Serra-sitjar M, Rodríguez J, et al. The tumour suppressor foxo3 is a key regulator of mantle cell lymphoma proliferation and survival[J]. Br J Haematol, 2012, 156(3): 334-45. doi: 10.1111/bjh.2012.156.issue-3

[23] Jiang Y, Zou L, Lu WQ, et al. Foxo3a expression is a prognostic marker in breast cancer[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(8): e70746. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070746

[24] Miller BH, Wahlestedt C. MicroRNA dysregulation in psychiatric disease[J]. Brain Res, 2010, 1338: 89-99. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.03.035

[25] Feng S, Jin Y, Cui M, et al. Lysine-specific demethylase 1 (lsd1) inhibitor s2101 induces autophagy via the akt/mtor pathway in skov3 ovarian cancer cells[J]. Med Sci Monit, 2016, 22: 4742-8. doi: 10.12659/MSM.898825

[26] Marlow LA, von Roemeling CA, Cooper SJ, et al. Foxo3a drives proliferation in anaplastic thyroid carcinoma through transcriptional regulation of cyclin a1: A paradigm shift that impacts current therapeutic strategies[J]. J Cell Sci, 2012, 125(18): 4253-63. doi: 10.1242/jcs.097428

下载:

下载: